Insider's Game

Selected writings by David Fiderer

How Goldman Dissembled In The Wall Street Journal

First published in ZeroHedge on June 7, 2011

The Wall Street Journal story, “Goldman Plans to Fight Back Against Senate Report,” which references the Levin Report on the financial crisis, is somewhat misleading. Consider this excerpt:

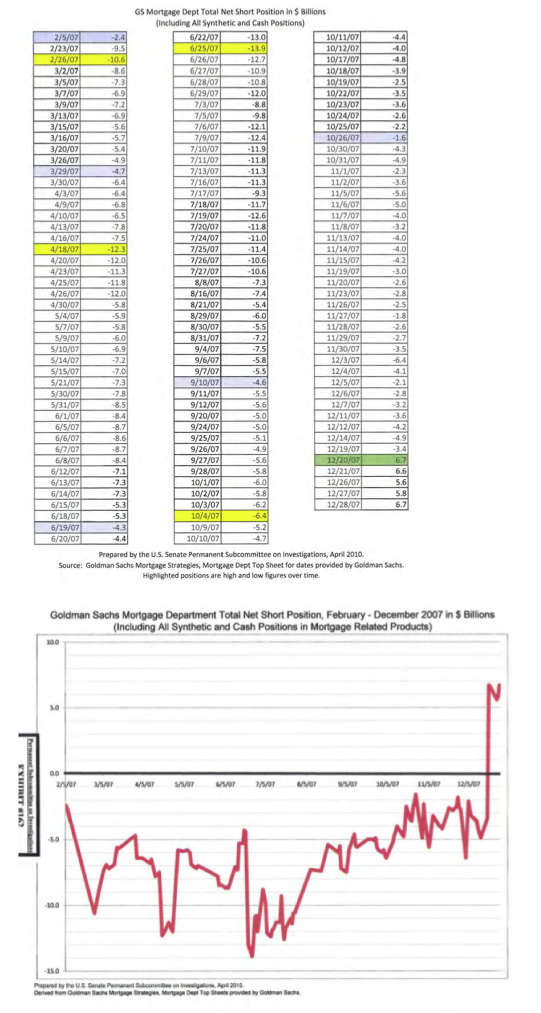

For example, one of the most dramatic documents released by the panel is a chart showing the size of Goldman’s overall long or short bets on the housing market. While those bets varied from day to day, the Senate subcommittee said Goldman had net short positions of $10.6 billion on Feb. 26, 2007, and $13.9 billion on June 25, 2007. The June 25 position was the company’s biggest bet against the housing market, according to the Senate subcommittee.

Goldman now plans to contend that both figures are wildly inaccurate, claiming Senate investigators overlooked or ignored bullish mortgage trades held by the securities firm, these people said. Documents detailing those bets were submitted to the subcommittee, but few of them were released as part of the April report.

The document in question, below, that was not part of the 2011 report. It was released one year earlier, on April 27, 2010, when the Subcommittee held hearings on Goldman’s trades. (See Exhibit # 162.)

After those April 2010 hearings, the subcommittee drilled down further. It came to recognize that The Big Short was never a “bet against the housing market.” Goldman and its cohorts were far more focused. They did not bet against housing, or against subprime bonds in general. Instead, Goldman took a massive short position the BBB and BBB- tranches of subprime bonds. These were the toxic assets with 20 times leverage that were stuffed in to mezzanine CDOs. Once the housing bubble stopped, these BBB defaults became virtual certainty. Goldman was a leader in fabricating synthetic mezzanine CDOs, insuring BBB tranches, which were designed to fail.

The Journal continues:

For June 25, 2007, Goldman officials believe Senate investigators didn’t take into consideration more than $5 billion of prime, or high-quality, mortgage-backed bonds held by the firm at the time, another document shows.

Here Goldman is trying to suggest some kind of false equivalency between credit risk of prime mortgage bonds (about which we have no information) and the hyper-leveraged BBB tranches on subprime bonds. No one ever believed that subprime mortgages performed in tandem with the prime market. These two positions do not offset one another and any more than a position in natural gas offsets a position in asphalt.

Finally, Goldman’s pushback seems more than a little disingenuous, given the extent to which it dragged its feetand stonewalled investigators who sought information. Exhibit A is Goldman’s response to a request by the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission about the firm’s trading data. Goldman offered up a tally of 22,000 trades, but excluded information on:

- Whether a trade was long or short;

- The identification of the counterparty; and

- The identification of the ABX instrument being traded.

Which is why it was no surprise last week when Lehman Brothers Holdings accused Goldman of intentionally delaying the disclosure of documents.