Insider's Game

Selected writings by David Fiderer

Dirty Little Secrets About Goldman’s Collateral Calls on AIG

First published in ZeroHedge on January 25, 2011

When it comes to AIG’s liquidity crisis, Wall Street’s conventional wisdom absolves Goldman from blame. Goldman’s people, so the story goes, were smart and therefore prescient about the declining values of CDOs. So their demands for cash margin from AIG, which insured billions of toxic CDOs for Goldman’s benefit, were legitimate. By contrast, AIG’s people, the poster boys for financial incompetence, kept flailing about because they were in denial until everything reached a crisis point in September 2008.

Yes Goldman was smart, and yes, the people at AIG were clueless, which is why Goldman could pull off such an audacious scam. Goldman’s demands for margin were made in bad faith, and possibly under fraudulent pretenses. The conventional wisdom overlooks a critical point: The legal documents had no teeth and might have been impossible to enforce.

The problems with the documents, in the context of the overall business deal, require a bit of explanation. But it’s worthwhile to remember that all these deals are governed by two truisms: First, if you skip a step in analyzing a structured deal, you probably end up with the wrong answer. And second, almost everything about CDOs is kept secret in order to protect the guilty.

Transactions Designed to Prevent Any Sale On The Open Market

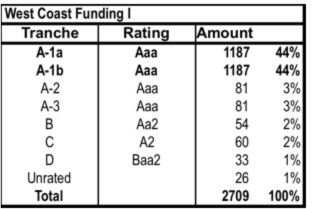

For a sense of how it all worked, consider West Coast Funding I, a $2.7 billion CDO that closed on July 26, 2006. This deal, which was underwritten and structured by Goldman, was exactly like 100 others taken on by AIG. West Coast I had seven rated tranches, of which the most senior four, representing 94% of the total deal, were rated triple-A. The two most senior tranches, A-1a and A-1b, were called “super-senior” because they ranked higher than the other triple-A slices. The exact amount of tranche A-1a was $1,187,950,000. The exact amount of tranche A-1b was $1,187,950,000.

One week before West Coast Funding I closed, on July 19, 2006, AIG Financial Products entered into two credit default swaps with Goldman Sachs International. The trades would be effective on July 26, 2006, the date on which West Coast I first came into existence. Effective that date, AIG insured $1,187,950,000, or 100%, of tranche A-1a, and $1,187,850,000, or 99.992%, of tranche A-1b. The entire super-senior tranche, about 88% of the CDO, was insured for the benefit of one bank on the same day that the CDO closed or came in to existence. This was the fixed template, from which there was almost no deviation, on virtually all of the “multi-sector” CDOs insured by AIGFP.

There was never a single day when anyone, other than AIG, ever took the direct credit risk on the super-senior tranche. The essence of the transaction, the business model for all these deals, was to preempt the possibility that the super-senior tranches could ever be sold on the open market. The West Coast I Offering Circular, issued weeks later on September 16, 2006, gives no indication that 88% of the credit risk was insured by AIG, which also extended interest-rate swaps to the CDO. Again, almost everything is kept secret in order to protect the guilty.

Goldman claimed that it “sold” these tranches to third parties, but that half-truth is highly deceptive. After the deal closed, Goldman held two assets: The super-senior tranches and the credit default swaps. As the insured beneficiary, Goldman would never sell the tranche free and clear on the open market. These particular credit default swaps required physical settlement; Goldman was required to physically deliver title to the tranche securities before it could recover any insurance proceeds in case West Coast I defaulted. If Goldman lost control of the super-senior tranches of West Coast I, its swaps could become worthless.

So Goldman never sold West Coast I, or any of the other insured tranches, free and clear to anyone else. The asset “sales” were structured so that title would revert back to Goldman when it needed to collect on the swaps. In the case of West Coast I, it entered into a series of tie-in sales, package deals that assured Goldman’s ability to take back title to the asset in case an insurance claim ever came due. Nominally it “sold” pieces of West Coast I to some obscure European institutions, and simultaneously insured those pieces with credit default swaps. The “buyers,” ZurcherKantonalbank, and Depfa Bank and Zulma (see Tab 39 of FCIC exhibits) had no significant presence in the U.S. residential mortgage market. But they weren’t concerned. From their credit perspective, the package deal was pretty much the same thing as buying a bond from Goldman Sachs, with some extra collateral attached. At the point when the CDO defaulted, the European “purchasers” would be reimbursed by Goldman, after they physically delivered back to the investment bank.

West Coast I was unlike many other Goldman CDOs, in that the insured beneficiary was also the bank that structured and underwrote the deal. More often than not, Goldman deals were not insured for the benefit of Goldman, but for the benefit of Societe Generale, which worked closely with Goldman to create the illusion of a real CDO market, one where banks went through the motions of buying and selling the super-senior tranches. Goldman would sell the entire super-senior tranche on a CDO’s closing date, and SG would simultaneously close on an AIG swap insuring the entire tranche amount. SG never really “bought” anything free and clear, in that it never assumed one dollar’s worth of direct credit risk on Goldman deals for even one single day. Goldman “sold” about $11 billion worth of CDOs for SG this way. It also “sold” another $4 billion worth of CDOs to another French bank, Calyon. But the only party that took direct credit risk on the CDOs was AIG.

Most of the deals insured for Goldman’s benefit were underwritten and structured by Merrill Lynch, which was largest CDO underwriter on Wall Street. But again, Goldman “purchased” the entire super-senior tranche on the same day that the CDO was created, and on the same day that AIG insured the entire amount. It didn’t matter how large or how small the tranche was, Goldman bought the entire amount and AIG insured the entire amount, and the swap required Goldman to hold on to the tranche in order to collect insurance proceeds. So there was never a moment, when any of these deals could ever be bought or purchased, free and clear, on the open market.

The Impossibility of Measuring An Undefined “Market Value” When Neither the Assets, Nor the Market, Ever Existed

In making its demands for margin, Goldman calculated the value of West Coast I as an asset that was entirely separate from its AIG guarantee. But that asset had never existed in the real world. No one had ever bought or sold those tranches severed from the umbilical cord of a double-A corporate guarantee. When people talk about “market value,” they talk about an external reality check from a bona fide market, one dominated by arm’s-length purchase/sale transactions, and one with a cash basis, where price discovery is ascertained by people laying out real money. The CDO market, at least the market for the $70 billion worth of super-senior CDO tranches insured by AIG, was nothing more than an illusion.

Was the concept of market value even relevant? Not according to PriceWaterhouse Coopers, the auditor for both AIG and Goldman. It had determined that, under current accounting standards, the fair value of these CDOs could not be measured according to comparable sales or market benchmarks. These were “Level 3” assets, meaning that the only appropriate way a company could measure the assets’ value was on a fundamental basis, through financial models developed internally by AIG or Goldman.

Aside from the absence of any real market, or any commonly accepted measure of market value, there was no definition of “market value” in the contracts between AIG and Goldman. The term “market value,” is rarely self evident in swap contracts that reference financial instruments traded in real markets. Those contracts don’t simply reference the market price of oil; they reference the closing price of West Texas Intermediate quoted at close of the trading day on the NYMEX. They don’t simply reference Libor, but JPMorgan Chase 30-day Libor. But the contracts between Goldman and AIG offered no guidance for measuring the market value of the CDOs.

But even if we assume that someone could establish a theoretical market value based on a company’s internal financial model, which model would prevail? Neither one. No single party decided what the market value actually was; Goldman and AIG both decided. Both companies were designated as the “Calculation Agent” in the swap confirmations. (AIG was the exclusive Calculation Agent for swaps conducted with SG.)

Goldman and AIG could debate the value of West Coast I, and all the other CDOs, and then, after failing to agree, each side would appoint its independent representative, who would then take a while to deliberate on the valuation. If they failed to agree, the two representatives would deliberate over the choice of a final, single arbiter, who would then ascertain the value of the CDO tranche, at a point long past the date of the initial dispute.

It wasn’t only the “market values” that might shift over time; the investments within the CDO portfolios could easily shift as well. Most of the CDOs insured by AIG were managed, meaning that they were run by asset managers who had great latitude to substitute different investments within the CDOs. So each time the assets changed, a brand-new valuation was necessary. So nothing about the CDOs’ valuations, in a nonexistent market, could ever be pinned down. So nothing could ever be settled, except in court or in arbitration.

And if there’s no way to attain a timely resolution, then the margin requirements seem meaningless. In real markets that trade with a cash basis, the need for timeliness can be easily measured. If you pay less attention to the form and focus the underlying substance of the transactions, which were governed by vague and sloppy wording, you have to wonder whether Goldman’s demands for margin would have been enforceable.

But Goldman’s management didn’t care about the contract language. It wanted AIG to hand over cash, sooner rather than later. And they pulled out the stops to pressure into everyone into accommodating their dubious demands.

How Goldman Tried to Scam AIG

A few days after executives at Goldman made their initial demands in July 2007, they started playing hardball with Tom Athan of AIGFP. “Tough conf call with Goldman,” he emailed afterwards. “They are not budging and are acting irrational.” The issue was a “test case” that had gone to “the highest levels” at Goldman. But–here’s the smoking gun–Goldman insisted that AIG present it “actionable firm bids and firm offers” to come up with a “mid market quotation,” for valuing the insured assets. The idea was patently nonsensical. There never were and there never would be any bona fide bids of any kind, be they “actionable and firm,” or merely “indicative,” because no one ever intended to buy or sell the assets, which were never available for sale on a free-and-clear basis. But the people at AIG never put two and two together. Like a bunch of suckers, they went out soliciting “quotes,” which Merrill Lynch would only offer on a confidential basis. They also got quotes from Goldman and SG.

Goldman clearly wanted to override the wording of the documents, which prevented the bank from asserting the upper hand, according to reporting in The New York Times:

[David] Viniar, Goldman’s chief financial officer, advised the insurer in the fall of 2007 that because the two companies shared the same auditor, PricewaterhouseCoopers, A.I.G. should accept Goldman’s valuations, according to a person with knowledge of the discussions.

When A.I.G. asked Goldman to submit the dispute to a panel of independent firms, Goldman resisted, internal e-mail messages show. In a March 7, 2008, phone call, [AIGFP CEO Joe] Cassano discussed surveying other dealers to gauge prices with Michael Sherwood, Goldman’s vice chairman. At that time, Goldman calculated that A.I.G. owed it $4.6 billion, on top of the $2 billion already paid. A.I.G. contended it only owed an additional $1.2 billion.

Mr. Sherwood said he did not want to ask other firms to value the securities because “it would be ’embarrassing’ if we brought the market into our disagreement,” according to an e-mail message from Mr. Cassano that described the call.

The Goldman spokesman disputed this account, saying instead that Goldman was willing to consult third parties but could not agree with A.I.G. on the methodology.

As noted here eariler, you need to take everything Cassano says with a pound of salt, especially since he “retired.” three days after sending the e-mail in question.

Nonetheless, it sure looks as if Goldman has been trying to scam the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission in much the same manner that it scammed AIG, with a lot of dissembling about “market values.” Again, Goldman’s auditor, PriceWaterhouse and, Deloitte & Touche, the auditor for Maiden Lane III, the entity holding the toxic CDOs once insured by AIG, found that these assets had no “market value;” they could not neither be measured according to actual sales nor comparable sales of similar assets in the marketplace. The only valid way to ascertain their fair value would be to perform fundamental cash flow analyses.

Why Goldman Never Shares Its Cash Flow Calculations With Anyone Else

There’s no indication that Goldman shared its cash flow evaluations with AIG or with anyone else. A lot of documents have been released so far by Goldman, the FCIC, the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, and the Congressional Oversight Panel. None of those documents show any contemporaneous communication by Goldman to AIG about how the bank actually calculated the values of the CDOs. In its highly selective and misleading history of events written after the fact, Goldman glosses over the fact that the reference assets were never available for sale on the open market, and that its valuations based on comparable sales violated fair value accounting standards.

There’s no doubt that Goldman performed fundamental cash flow analyses on all its mortgage assets. As management relayed to the Board of Directors in a slide titled,”Independent Price Verification” :

A dedicated group within Controllers performs an independent price verification of the mortgage inventory. The team is highly specialized and has extensive experience in the valuation of mortgage related products…Price verification analysis utilizes four core strategies, [including] Fundamental analysis [which] utilizes discounted cash flow (DCF), option adjusted spread (OAS) or securitization analysis. Observable market data or inputs are incorporated when available and appropriate.

Almost certainly, the disclosure of those cash flows would have been damning, not because Goldman had overstated the declines in values of the CDOs insured by AIG, quite the opposite. It might have revealed how Goldman and others had been artificially propping up the values of toxic securities, as part of an elaborate pump and dump scheme.

Two years ago, Sylvain Raynes, formerly of Goldman and Moody’s and currently a principal at R&R Consulting, replicated the type of cash flow analysis done by Goldman and every major Wall Street bank. By statistically evaluating the cash flows of the 20 subprime bonds referenced in the ABX 2006-1 indices, Raynes calculated their composite values beginning in January 2006, when the ABX was first launched. Beginning in January 2006, all of the indices, aside from the AAA index, were worth pennies on the dollar. In December 2006, Goldman closed on its new $2 billion CDO, Hudson Mezzanine Funding I, which insured all of the BBB and BBB- bonds in the ABX at 100 cents on the dollar. In the months that followed, Goldman offered up ABACUS 2007 AC-1, Anderson Mezzanine Funding, and other toxic CDOs that were designed to fail.