Insider's Game

Selected writings by David Fiderer

Hank Paulson, The Unnamed “Decider” In The Merrill Lynch Saga

First published in The Huffington Post on April 15, 2009

In his sworn testimony, Bank of America CEO Ken Lewis said that the $3.6 billion bonus pool at Merrill Lynch was not his highest priority. Given that the phrase “Wall Street bonus” currently invokes greater revulsion than “Osama bin Ladin,” his answer is not likely to win him many friends.

Lewis: “If you could think about the context in which I was operating, I was not thinking about when bonuses were paid.”

Question: “How about the amount of bonuses that were going to be paid?”

Lewis: “I wasn’t thinking about bonuses.”

Deposition for New York Attorney General, Andrew Cuomo

But Lewis has a point. Back in mid-December 2008, when Lewis considered backing out of the Merrill acquisition, bonuses were hardly the biggest issue on the table. His point about context is well taken. Many observers still don’t understand the drivers of Merrill’s fourth-quarter $21 billion pre-tax loss.

The standard media narrative is that Lewis and former Merrill CEO John Thain pulled a fast one, by withholding information of the brokerage firm’s downward spiral, and by pushing through the bonus payouts before the dire situation became public. That narrative is incomplete.

Without question, Lewis and Thain could have been more forthcoming. “The market conditions were generally known,” testified Thain, when asked why Merrill adhered to its business-as-usual policy – no projections, no earnings guidance, no interim results – during the fourth-quarter meltdown. If market conditions were known, they certainly were not well understood, then or now. And though the bonus pool was not finalized when Merrill responded to a congressional inquiry in late November 2008, Merrill’s claim, that no decision about bonuses had been made, was disingenuous at best.

Now the SEC, Andrew Cuomo and a litany of securities lawyers are all investigating whether a lack of timely disclosure of constituted violations of law.

But everyone – the investigators along with Lewis and Thain – seems to be intent on ignoring the elephant in the room, the guy who made the key decisions, Hank Paulson. The former treasury secretary’s actions drove the transaction from inception to closing, and triggered a big part of Merrill’s fourth-quarter losses.

Both Lewis and Thain operated under the constraints set by Paulson, whose role in the Merrill/BofA merger process was far more central than, say, Dick Cheney’s role in starting the Iraq war. When Thain, and later Lewis, expressed reluctance about the merger, Paulson responded with not-so veiled threats, according to reporting by The Financial Times and Fortune. Irrespective of what was said during those confidential meetings, it’s clear that the former Treasury Secretary’s public actions drove the business premise for the Merrill/BofA merger, and a major part of Merrill’s fourth quarter loss.

Until we come to grips with the actions taken by Paulson, we won’t have a clear picture of either Merrill’s loss of independence or the financial meltdown.

Paulson’s Two Decisions That Triggered Market Paralysis: Lehman’s Bankruptcy and the TARP Bait-and-Switch

At 6:15 p.m. on Friday September 12, 2008, Paulson blindsided Wall Street by announcing that the government would not consider providing any support to forestall a Lehman bankruptcy. This boxed all parties hoping to arrange a sale of Lehman, and made its Chapter 11 filing an inevitability. As Thain later explained in his sworn testimony, he figured out on Saturday September 13th that Lehman’s bankruptcy would cause a crisis in market confidence that could destabilize Merrill’s liquidity position.

Nouriel Roubini expressed the exact same view in the September 14 Sunday Times:

“‘In principle Lehman should be allowed to go,’ said Roubini. ‘But if that happens the next day there will be a run on Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs. Let’s not pretend that’s not going to happen. The systemic risk is worse now than it was with Bear Stearns. It’s pretty pathetic really.'”

Thain and Roubini would be proved correct by the end of the week. Lehman’s downfall on September 15 immediately destabilized the money markets and the interbank lending markets, before threatening the global financial system. It was only this sudden risk of market meltdown that created for Thain a new sense of urgency to merge with a stronger entity, as a way of avoiding the kind of fate that would soon befall Washington Mutual and Wachovia.

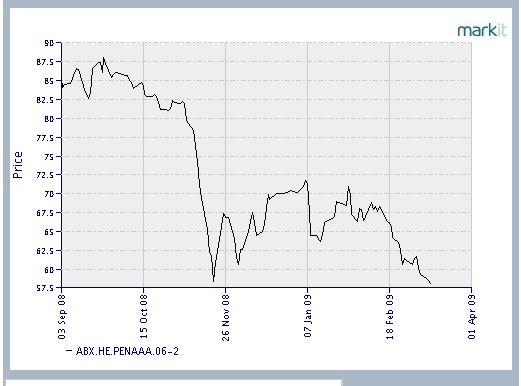

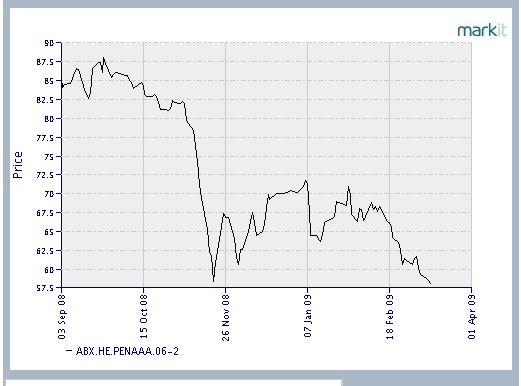

Two months later, on November 12, 2008, Paulson gave financial markets a second punch in the stomach. He did an about-face and said he would not use TARP funds to help arrest the downward spiral in mortgage asset values. All mortgage securities immediately went into a free fall, as exemplified by the nearly vertical line in the graph immediately below.

If you understand this graph, you can understand what wiped out the equity of Merrill and other major banks in late 2008. This illustrates how the markets for mortgage securities and credit default swaps intersect, and how fair value accounting methodology can easily morph from reality to theory to fiction. (A more detailed explanation of the phenomenon follows later in the piece.)

Cuomo’s Incomplete Recounting of Merrill’s Final Days Under John Thain

Cuomo’s chronology of events, set forth in a recent court filing, sidesteps Paulson’s role, and creates an incomplete and misleading narrative of Merrill’s downfall and the larger financial meltdown.

Here’s Cuomo’s chronology, with direct quotes lifted from the court filing.

September 13 – 14, 2008: BofA conducts due diligence of Merrill, and negotiates an acquisition agreement. “Time was of the essence for Merrill, as the company was not likely to survive the following week without a merger.”

September 15, 2008: Merrill and BofA publicly announce their merger agreement, without disclosing the provision for bonuses. “In an undisclosed portion of the Merger agreement, Bank of America agreed to grant Merrill the right to award bonuses of up to $5.8 billion to its employees for the 2008 calendar year.”

November 11, 2008: Merrill’s Compensation Committee decides to accelerate payout of bonuses so that they occur in 2008, before the merger with BofA.

November 24, 2008: Merrill tells Congress “no decision has been made” on bonuses. Merrill’s November 24,2008 letter represented that “Merrill Lynch operates on a calendar-year basis. The Management Development and Compensation Committee of the Board of Directors makes incentive compensation decisions at year-end. Consistent with this calendar year-end process, incentive compensation decisions for 2008 have not yet been made.”

December 5, 2008: Merrill’s shareholders approve the merger.

December 8, 2008: Merrill’s Compensation Committee sets bonuses that total $3.6 billion.“After Merrill set its bonuses on December 8, 2008, it quickly and quietly booked billions of dollars in additional losses.”

December 14, 2008: “Ken Lewis was advised that Merrill had lost several billion dollars since December 8, 2008. In six days, Merrill’s fourth quarter losses skyrocketed from $9 billion to $12 billion….Merrill’s fourth quarter 2008 losses turned out to be $7 billion worse than it had projected on December 8, 2008…Nevertheless, Merrill’s decision to payout $3.62 billion in bonuses prior to the close of year-end was never changed or even revisited.”

December 29, 2008: Merrill pays out 2008 bonuses. For the first time, Merrill’s bonuses were paid out in the same calender year as when they were earned. The payout occurred before BofA’s acquisition of Merrill took place.

January 16, 2009: Merrill’s fourth quarter losses are announced. Only then did Congress and the public learn about the fourth quarter losses and the early payout of bonuses.

What Cuomo Left Out or Mischaracterized

Here’s that same scenario, supplemented by press reports and witness testimony.

September 12, 2008: Fortune: Paulson preempts any discussion of any government support to facilitate a Lehman merger outside of bankruptcy. Despite Paulson’s stated refusal to provide government support, Lehman and Barclays had negotiated a privately financed deal by 9:00 a.m., Sunday, September 14. The deal required the blessing of the U.K. Financial Services Authority. But Paulson was unwilling to offer any time of support to help the the FSA backstop the risk and he declared the deal dead within 45 minutes. According to one of Fortune’s sources, the “FSA was looking for some kind of a cap to avoid U.K. contagion, and the Fed had just said, ‘No assistance for Lehman.’ The FSA then concluded based on the amount of diligence, the risk profile, and the lack of any assistance from the U.S. that they were not going to let it proceed.”

September 13, 2008: Thain anticipates that Lehman’s demise will destabilize markets and lead to a liquidity crunch at Merrill, so he seeks a merger partner. Thain’s testimony reveals two critical points: First, contrary to Cuomo’s suggestion, Thain did not believe Merrill was in a crisis situation before Lehman’s unexpected bankruptcy foreshadowed a market meltdown.

Second, Thain was concerned about Merrill’s liquidity, (i.e. its continued access to short-term unsecured credit) not its solvency (i.e. positive net worth). The fourth-quarter market losses that would threaten Merrill’s solvency would be triggered two months later.

September 13, 2008: The Financial Times: Paulson pushes Thain into pursuing a merger with BofA.

“Late on Saturday morning September 13, as Wall Street’s most prominent bankers met at the New York Federal Reserve to hatch a rescue plan for Lehman, Mr. Thain says it dawned on him that Lehman would not be rescued, so he called BofA’s Mr. Lewis to initiate talks. But several people present say Mr. Paulson first took him aside and gave him a stern talking to. These witnesses, who represented different parties in the talks, add that it was only after Mr. Thain returned from his one-on-one with Mr. Paulson, looking somewhat shaken, that he placed the call to Mr. Lewis.“

Thain had been Paulson’s protege at Goldman Sachs.

September 14, 2008: The Financial Times: Paulson to Thain, “Merge or else.”

“At the Fed that [Sunday] morning, Paulson laid it on the line with Thain: Merrill’s very existence depended on whether or not he could cut a quick deal. To more than one observer, Thain seemed shaken by the weekend’s events. For the New York Fed official who had described Thain as a ‘stone-cold killer’, the transformation of the Merrill chief executive over the weekend was remarkable. ‘He had lost his confidence,’ the official said.”

September 14, 2008: The Financial Times: Before the global meltdown, both sides agreed to one last hurrah for a traditional Wall Street bonus pool.

“One of the key issues in the acquisition agreement concerned the payment of bonuses. By selling to BofA, Merrill’s executives knew that the days of multi-million-dollar bonus payments would come to an end. As a concession, in a non-public side-agreement, BofA allowed Merrill to pay out bonuses of about $4bn before the deal closed. Neither Lewis nor Thain realized that this small amendment to the contract would eventually spark a state investigation requiring them and others to testify under oath about what they knew about the payments and when they knew it.”

[Unspecified date] The Financial Times: BofA tells Merrill to pay out bonuses before the merger.

“The board did agree to $3.6bn in bonuses to be paid out to other Merrill Lynch executives. At BofA’s request, most of the money would be paid out in cash later in the month, before the deal closed. The early payment would actually reduce expenses for BofA in 2009, making it easier for the bank to hit its first-quarter numbers.”

November 12, 2008: Paulson’s about-face on TARP funds causes a mortgage securities to collapse, and wipes out the equity of the major banks.

When Hank Paulson announced that he would not use TARP funds to help arrest the foreclosure crisis, market values of mortgage securities collapsed. The resulting losses threatened the solvency of Merrill and other large banks.

“The credit market was thrown into turmoil by Henry Paulson’s sudden changes to the $700bn Troubled Assets Relief Programme, announced late on Wednesday…’Paulson has really messed up everything. His news really couldn’t have been worse for financials,’ said a credit trader in New York yesterday…

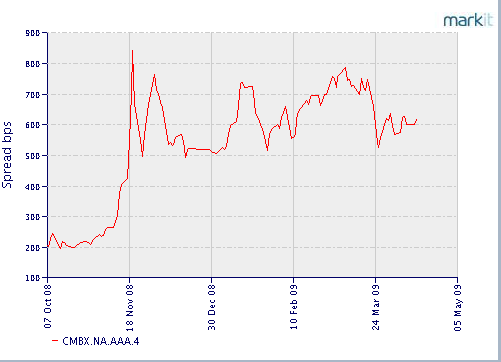

“If the banks were hard hit by the news, the indices that track distressed and mortgage related assets were cratered. ‘This has really not been good news for ABS and CMBS. It has sold off pretty fast,’ said a London credit trader yesterday. The triple-A portion of the ABX dipped below 37 yesterday, a level described by Citibank analysts as ‘truly shocking’.” “Banks count cost of Paulson’s Tarp U-turn’,” EuroWeek , November 14, 2008

Markit’s ABX HE PENAAA 06-02 index of first lien subprime mortgages is a typical benchmark for valuing all sorts of mortgage investments similar to those held by Merrill.

Notice how the slope of the line becomes almost vertical by mid-November. The decline in value between November 3 and November 20 was 29%. This kind of precipitous free-fall, among the very safest tranches within this type of AAA-rated securities, was unprecedented. Declines of similar magnitudes were seen in all for types of mortgage securities, such as the CMBX index for commercial properties, which is quoted according to capitalization rates.

After November 20, benchmark prices started shooting upward, reflecting an unprecedented level of price volatility. Nobody felt very confident about measuring the true economic value of these mortgage instruments. (For the best explanation anywhere on the problem, read “Valuations and Fundamentals,” by Laurent Clerc from the Banque de France.)

December 5, 2008: Merrill sets up projections for fourth-quarter earnings. Management expects that prices on mortgage securities will continue to rise above their current level.Billions of dollars in reported earnings, or losses, depend on the assumption that these mark-to-market positions will continue to recover. This information was inferred from Lewis’s testimony, directly below.

Why would Merrill’s senior management, with BofA’s acknowledgment, base their internal year-end projections on the assumption that securities prices would recover so sharply? Here’s my tentative hypothesis explained in very simple terms: They didn’t believe that the price quotations were real. That is, they thought the ABX quotes were completely disconnected from their underlying economic value, and that the market irrationality would reverse itself.

Think of it this way. When you own shares in IBM, you know exactly how much they are worth, because identical shares were openly sold in a transparent marketplace. When you own a mortgage on a foreclosed residential property, you can estimate your recovery based on a proxy, comparable home sales in that neighborhood. When you own mortgage-backed securities for which there is no readily available market, you use a proxy like the ABX index, adjusted by a dynamic financial model. Except the ABX index does not reference cash sales of houses or other mortgage securities; it’s a quoted price for credit default swaps based on a relatively small portfolio of mortgage securities. The market for this type of credit default swap, sold by companies like AIG, also became frozen. So this proxy no longer seemed valid.

Also, it was apparent to anyone who understood the situation that Paulson’s announcement threatened the banks’ solvency and that the government would need to reverse itself, as it had in the days following the Lehman bankruptcy. But Paulson, like his boss, had an aversion to admitting mistakes, and instead used other methods to paper over the problem with Merrill, as shown below.

December 14, 2008: BofA’s CFO tells Ken Lewis that there are not enough days before year-end for Merrill’s mark-to-market positions to recover. So Lewis considers backing out of the Merrill acquisition.

From Lewis’s deposition at Andrew Cuomo’s office:

Q: Did there come a time when you considered undoing the merger between Bank of America and Merrill Lynch?

A: Yes.

Q: When did you first consider doing that?

A:…. I’m pretty sure it was December 13th…[later corrected to December 14th] and what triggered that was that the losses, the projected losses, at Merrill Lynch had accelerated pretty dramatically over a short period of time, as I recall, about a week or so.

Q: How did you learn of that?

A: Joe Price, our CFO, called me. … He basically said what I just said.: The projected losses have accelerated dramatically. We earlier on had more days on the month so that at least some of the marks would come back, but now we had not very many business days because Christmas was coming and all that. So we became concerned just of the acceleration of the losses…To the extent that I remember, the losses had accumulated to about $12 billion after tax.

Q: Were you getting a daily P and L at the time?

A: We were getting projections,…we had a forecast on December 5, as I recall, of $9 billion, but $3 billion pre-tax was just a plod (phonetic) [plug?] just for conservative reasons; so what you saw was basically a 7 to 12 if you could go through the plod, and then you get to $12

billion. So a staggering large percentage of the original amount in a very short period of time.

What should have been publicly disclosed by BofA or Merrill at that time? The major issues remained unsettled and potentially reversible so that, perhaps according to counsel’s advice, the most appropriate course may have been to defer comment.

December 17, 2008: Fortune: Paulson and Bernacke tell Lewis the Merrill deal cannot be stopped or renegotiated.

“Lewis feared that BofA no longer had enough capital to absorb a damaged Merrill. On Wednesday, Dec. 17, he flew to Washington to discuss his options. At 6 p.m., he sat down with Fed chairman Ben Bernanke and Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson.

“Bernanke and Paulson weren’t swayed. They told Lewis that the Fed’s legal staff had read the contract, and that under the law, BofA absolutely had to close the deal. They also said that a failure to buy Merrill would put the entire banking system at risk. They made it clear that renegotiating the price – a natural move in normal times – was not an option. The reason: It would take two months to issue new proxy statements and hold shareholder votes at both companies, while the fate of Merrill stayed in limbo. Bernanke and Paulson said they would provide a rescue package for BofA to ensure that it had adequate capital to complete the deal.

“Technically the government did not have the authority to force Lewis to buy Merrill. But it hardly matters: In the current crisis bankers have little alternative but to do what Washington tells them. ‘The Fed and Treasury made it crystal clear,’ says one person familiar with the talks. ‘Our position is your position.'”

This is the critical part. Merrill’s acquisition price included the $3.6 billion cost of the bonus payout. By telling Lewis he could no longer renegotiate the price, and that the Feds will make up any shortfall in capital adequacy, Paulson and Bernacke effectively sidelined the bonus issue.

And what can Lewis or Thain say now? Neither can easily claim, “I would have done things differently, but Hank Paulson backed me into a corner.”