Insider's Game

Selected writings by David Fiderer

Prosecuting The Rating Agencies: A Roadmap Through Three Big Falsehoods

First published in OpEdNews on August 30, 2011

Dear Justice Department,

So far, major investigations by the S.E.C., by the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission, and by the Senate Subcommittee on Permanent Investigations have let the rating agencies off the hook. They found that the agencies were far less diligent and conscientious than they should have been, and were therefore slow to appreciate the implications of the real estate bubble and slow to take corrective action. In other words, they failed to do their job but they weren’t crooked.

Top rating agency executives, who have no shame, disagreed. Moody’s CEO Ray McDaniel, whose travesty of corporate governance helped cause damage 100 times worse than that caused by Enron or the Madoff Fund, refused to accept any real blame. Neither he nor his top deputies have been held to account for their malfeasance and their cover-up.

Now, your new investigation presents a chance to pick up where the others left off. This letter offers a roadmap for jumpstarting the process. One pitfall you want to avoid is getting bogged down with the incessant dissembling from rating agency executives. If you listen to the FCIC interviews of the top people at Moody’s, you’ll notice that they talk forever but refuse to be pinned down on anything. They are very clever and adept at muddying the waters. But as we’ll see, it is very easy to prove that virtually every single subprime and Alt-A mortgage securitization, and every single CDO comprised of mortgage securities, was rated under false pretenses.

Numbers Frame The Narrative

To proceed, you need to think like Harry Markopoulos, who, upon reviewing the preposterous financial results of the Madoff Fund, said, “I knew he was a fraudster in five minutes.” Remember, in finance and business the narrative is always framed by the numbers, not by what people say. And if you start with the numbers and work backwards, it quickly becomes apparent how people were lying and deceiving.

Markopolos did have that rarest of rare qualities, a willingness to say that the emperor has no clothes. Over the past decade, few have been willing to declare that the emperors who defined reality in mortgage finance had no clothes. And from what I’ve been told, many who wanted to speak out were fearful of retribution or blacklisting.

Thankfully, the numbers on mortgage securities, reduced to their bare essentials, are easy to understand. You don’t need an advanced background in statistics to prove that the ratings processes had devolved into a complete sham. If you let the numbers frame your inquiry, you won’t find a single smoking gun; you’ll find thousands of smoking guns.

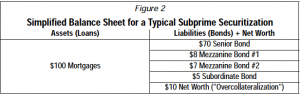

Here’s simple but emblematic example, a deception that was repeated by Moody’s executives Warren Kornfeld, Michael Kanef and Jay Siegel. When people started getting nervous about the sector, they presented the “Typical Subprime Securitization,” which was structured with 10% equity, or overcollateralization.

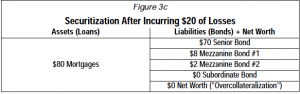

Such a thing never existed. There never was any “Typical Subprime Securitization” structured to close with 10% overcollateralization, just as there was never any “typical ballerina,” who weighed 300 pounds, or any “typical McDonalds hamburger,” priced at $50. The initial equity tranche or overcollateralization on any subprime deal was invariably between 3% or 4%. These Moody’s executives wanted to promote the false impression that the structures and ratings were devised with some reasonable margin for error, which was definitely not the case. The deals were structured with virtually no margin for error, because they relied on garbage-in/garbage-out ratings methodologies.

Their example also showed that if a mortgage pool incurred a 20% loss, the “senior bond” would not be impaired. In fact, a 20% loss meant that all of the principal on tranches rated double-A, single-A and triple-B got wiped out. When Kormfeld first presented this example on April 19, 2007, a total writeoff on a double-A-rated bond seemed unimaginable. And by April 19, 2007, it was clear as day that every single subprime mortgage bond issued during the past two years would suffer big losses on its investment grade tranches.

This “typical subprime securitization” falsehood touches on two of The Three Big Lies Falsehoods, which are rating agency mantras. They are:

1. We rated these mortgage securities in good faith;

2. Our ratings on structured deals are merely opinions, protected by the 1st Amendment; and

3. We downgraded these mortgage securities on a timely basis.

By suggesting that the deals had a reasonable margin for error, Moody’s suggested that the ratings were assigned in good faith (Number 1). And by suggesting that a deal could burn through a 10% loss rate before any rated debt tranches would be impaired, it suggested that the need to slash the ratings of subprime bonds in April 2007 was less than obvious, (Number 3). As you’ll see, the rating agencies put forth a variety of distortions that can be subsumed into these three categories of deceit, which all require further explication.

1. We rated these residential mortgage securities in good faith.

A Simple Example: Residential mortgage securitizations involve a number of moving parts, so before we get into all the conceptual issues, let’s start off with a concrete example of a preposterous rating. GSAA Home Equity Trust 2006-1, a $900 million transaction put together by Goldman Sachs, financed 3,965 Alt-A home mortgages. It’s substantially similar to hundreds of other Alt-A deals structured without any reasonable assurance that the borrowers could afford to pay back their loans, or that the loans had not been induced by fraud.

About 82% of the mortgage pool was comprised of “stated income” loans, aka liar loans. The remainder included loans that relied on “alternative” forms of documentation. About 89% of the loans were interest-only, which substantially reduced the borrowers’ monthly payments. To establish each borrower’s creditworthiness, the deal relied on FICO scores, which averaged 709. However, a FICO score is not based on a borrower’s income, and FICO scores are easily manipulated.

The borrowers financed, on average, 88% of the home’s appraised value, with: (a) about 78% from first lien mortgages held as collateral by GSAA 2006-1, and (b) another 10% in 2nd lien financing. A majority of the loans were located in four states–California, Florida, Arizona and Nevada—where home prices had doubled over the prior five years. Since all of the loans were originated by non-bank lenders, primarily Countrywide Home Loans and PHH Mortgage Corporation, the source of the down payments was not verified. Federal Anti-Money Laundering statutes applied only to depository institutions, like banks or S&Ls.

By adding up all those risk factors, “Moody’s expects collateral losses to range from 0.80% to 1.00%.” In other words, the expected loss on this deal was lower than the average expected loss observed on jumbo loans in the early 1990s. Which is how GSAA Home Equity Trust 2006-1 could be structured with 94% of the deal rated triple-A. Did Moody’s have any reasonable basis to believe that this pool of 30-year loans would incur credit losses in the range of 1%? No, none whatsoever. For anyone with a background in credit, or for anyone familiar with the concept “garbage-in/garbage-out,” this is obvious. As Markopolos said, you can figure out that something is really wrong in about five minutes. And Moody’s rated hundreds of Alt-A deals just like this one, for which it calculated an expected loss in the range of 1.5% or less.

As with the other rating agencies, Moody’s analysts were compelled to rely on a financial model that was rigged to produce the results desired by Wall Street clients. In theory, models are useful tools for analysts and managers. But in practice, the analysts are frequently subservient to the models or templates, and their primary job is to rationalize a consistency with the models’ design flaws. Now let’s go through the different ways that the rating agencies violated the basic rules of credit in order to award the bogus credit ratings that fueled the real estate bubble.

Rating Through The Bubble

The key to Michael Kanef’s testimony before Congress, and to Moody’s disinformation campaign, is embedded in the subordinate clause of this sentence:

“As illustrated by Figure 3, the earliest loan delinquency data for the 2006 mortgage loan vintage was largely in line with the performance observed during 2000 and 2001, at the time of the last U.S. real estate recession.”

There was no real estate recession in during 2000 and 2001. On July 6, 2000 the Mortgage Bankers Association announced that delinquencies had fallen to a 28-year low. Though overall delinquencies would rise thereafter, they remained low by historical standards, because home prices kept rising everywhere, even in the states affected by a severe manufacturing recession. Subprime delinquencies rose during 2000 and 2001, but they fell dramatically in the later part of 2001, when Greenspan began slashing interest rates and pushed home prices further upward.

A housing bubble conceals a multitude of sins. If a borrower can’t afford his monthly installments, he sells his house and recovers his equity. Or he refinances with a bigger loan based on a higher appraised value. Or he flips the house, in which he never intended to live, to secure a quick profit.

By using 2000/2001 as a benchmark, Kanef wanted to mislead Congress and the public into believing that Moody’s rated these deals “through the cycle,” that the ratings were calibrated according to how the deals would fare during a cyclical downturn. In fact, Moody’s, S&P and Fitch did the opposite. They rated through the bubble. In order for their ratings to work, the housing bubble had to continue its upward climb. If home prices experienced the gentlest of soft landings and fell even slightly, hundreds of billions of investment grade mortgage securities got wiped out.

Since time immemorial, real estate lending has been governed by two rules: (1) Location, location, location; and (2) Timing is everything. Simply put, after a loan is booked, the rate of home price appreciation, upward or downward, is the most important factor in determining whether a lender gets his money back. The impact is exponential. That is, when prices are rising at a brisk pace, the risk that a borrower will default is exponentially lower. And if a borrower does default in a rising market, then the rate of loss on any foreclosure sale is exponentially lower.

This is especially true in the subprime sector. Goldman’s rule of thumb was that every 5% of annualized home price increase reduced subprime defaults by 6% by the 6th year. In other words, Goldman’s data showed if home price appreciation ranged between 10% and 15%, the six-year cumulative default rate was about 5%; if price appreciation ranged 0% and 5%, the default rate was about 18%.

The risk of flat or falling home prices is much higher for private label mortgage securities than it is for bank lenders, who can diversify their market risk. An investor in a private label deal needs to worry buying loans at the peak of the cycle. A bank holds loans that were originated before the peak, and it can profit from new loans booked after the peak. And while private label deals are generally nonrecourse, GSE mortgage bonds have a guarantee from a bank, Fannie or Freddie, which holds loans originated throughout the cycle.

There’s another rule about residential real estate. There’s no such thing as short cycle. It goes through multi-year periods of feast or famine. If any real estate market experiences a feast of sharp annual price increases, a multi-year correction invariably follows. In 2005, the FDIC published a study titled, “U.S. Home Prices: Does Bust Always Follow Boom?” The answer was, “No,” because the FDIC defined a bust as a 15% price decline over a five-year period. But in every boom market, there was a subsequent multi-year famine when prices showed nominal appreciation or some kind of decline. And even though a bust did not always follow a boom, the correlation was very high.

In other words, by 2005 there was a mountain of evidence indicating that future home price the loss rate on newly-booked subprime mortgages would be several times higher than that observed for 1999 and 2000-vintage subprime mortgage deals, which had an average six-year cumulative loss rate of 6%. During the six-year stretch following 2000, the 20-city Case Shiller composite appreciated by 80%. But when Moody’s rated subprime deals in 2005 through 2007, the estimated loss was usually 6% or lower. For instance, the 20 deals referenced in the ABX 2006-2 composite had estimated losses ranging from 4.2% to 6.6%, with an average of 5.4%. In other words, Moody’s estimated losses to match the loss rate seen during the bubble.

When home prices stopped rising in 2006, subprime delinquencies spiked upward and it quickly became obvious that the lower-rated tranches of subprime bonds would default. But if Moody’s were going to issue downgrades, it needed a good explanation, something other than the truth, which was that they screwed up. So management began working on an elaborate strategy to rationalize what they had been doing all along. One of the foundations of this disinformation strategy was to benchmark loan performance based on data observed during the housing bubble, which is what Kanef, the former head of Moody’s structured finance, attempted to do in his written testimony.

Ignoring Leverage

The rating agencies found other ways to repudiate the truism that home equity drives loan performance, most notably when they decided that simultaneous second liens didn’t matter. From a credit or common sense perspective, this is like saying that the sun sets in the east or that water flows uphill. S&P’s press release, dated August 23, 2000, is a real gem of sophistry and doublespeak:

Standard & Poor’s Residential Mortgage group has revised the foreclosure frequency multiples it uses when determining loss coverage amounts for first-lien loans originated with simultaneous second-lien loans (simultaneous seconds)…The new criteria specify that…A first-lien loan with a simultaneous second lien will have its risk grade determined by the LTV of the first-lien loan and not by the CLTV.

In plain English, this means that an 80% first lien loan extended to a borrower who buys his home with a 20% cash down payment is no less risky than an identical loan extended to a borrower who finances the remaining 20% with a simultaneous second lien loan. Does anyone with half a brain really think that the second borrower is no more likely to walk away in case he fell on hard times or if home prices fell? In California and Arizona, a homeowner could walk away and the lender would have no recourse beyond the underlying real estate collateral. Mind you, there has always been a mountain of evidence that borrowers, of any kind, who have an appetite for high leverage also have an appetite for risky behavior that leads to default.

In theory, the second lien lender gets nothing until the first lien lender is fully repaid in a foreclosure sale. But, as Lew Ranieri explained to the deaf ears of rating agency executives, a second lien lender can throw a monkey wrench into any good faith efforts to work out or restructure a problem loan. Which is exactly what’s happening now.

How did S&P decide to gut this preexisting credit standard? Based on the selective disclosures of a few lenders during the time that mortgage delinquencies were at a 28-year low. It seems a safe bet that the hypothesis was not tested over the extended life span of a real estate cycle. One of the problems with second lien mortgages was that disclosure was inconsistent, so, in acknowledging that they didn’t know what they didn’t know, S&P assumed it wasn’t a problem.

Consistency That Strains Credulity

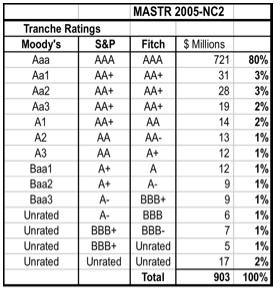

Markopolos didn’t believe that the Madoff Fund generated returns that were so remarkably consistent over time. The remarkably consistent credit ratings among mortgage securities also raise suspicions. Check out the capital structures and ratings of different Alt-A or subprime deals, and you’ll notice that they’re all very much alike, almost unbelievably so. With subprime deals, the top 80% is always rated triple-A, the next 10% is rated double-A, the next 6-7% is rated single-A and triple-B, with the remainder unrated. Here’s an example of two subprime deals, of a similar vintage, with vastly different risk factors and substantially identical ratings. It sure looks as if the models and methodologies were rigged to come up with the desired results, no matter what the inputs. Moody’s didn’t use a financial model for rating subprime deals until the bubble had peaked in 2006. Prior to that point, it used a benchmarking system that resulted in standardized cookie cutter results.

MASTR Asset Backed Securities Trust 2005-NC2 was a $903 million deal underwritten by UBS in November 2005. Consider that:

– 100% of the loans were interest-only.

– 100% of the loans were adjustable rate.

– 60% of the loans closed with second-lien financing. That 60% segment of borrowers had zero equity in their homes at the time of closing. (First lien loans in the MASTR pool financed 80% of the appraised value, while some other second lien-lenders financed the remaining 20%.) In the overall pool, the combined loan to value was 92%.

– 58% of the loans relied on “stated documentation,” meaning that the originator placed a phone call to verify that the loan applicant worked where he said he did. No income or net worth was ever verified.

– 55% of the loans were in California, where home prices had risen by 50% in the prior 24 months;

– The loan originator was New Century Financial, an unregulated mortgage lender in California. To qualify for New Century’s best category of credit risk, a customer with a 550 FICO score could file for a Chapter 7 bankruptcy one day before mortgage closing.

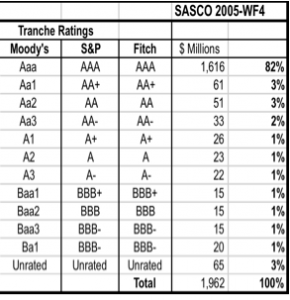

Now consider a deal issued by Lehman Brothers in September 2005, Structured Asset Securities Corporation Mortgage Pass-Through Certificates, Series 2005-WF4. At first blush, the capital structure looks only slightly different, at the margins.

Yet in this deal:

– 15% of the loans were interest-only,

– 74% were adjustable rate

– 5% closed with second liens,

– 93% of the loans had full documentation

– 14% of the loans were in California, the highest concentration of any state.

– The loan originator was Wells Fargo Bank. Unlike New Century, which was not subject to any real regulatory oversight, Wells Fargo was required by law to confirm the source of funds for any down payment on a prospective buyer’s new home. A lot of home flipping schemes involved down payments with laundered money.

– 73% of the loans had prepayment penalties.

Between these two deals, the differences in risk profiles were huge. But Moody’s declared the upward range of estimated loss on the MASTR collateral to be 4.4%, while the upward range on the SASCO collateral was 4.5%. Again, there are hundreds of examples that show how the risk variables within a mortgage pool had almost no impact on the eventual ratings or capital structure.

Ignoring Signs of Fraud, or Garbage-In/Garbage-Out Analyses

The MASTR deal illustrates how the subprime industry invited fraud. You cannot model fraud, because it never occurs in a random predictable manner, though it’s a safe bet that dishonest people take the path of least resistance. The rating agencies’ attitude toward fraud was the same as it was toward second liens: We don’t know what we don’t know, so let’s assume there’s no problem. Except it was impossible to follow the real estate industry and not know that it was a major problem. The epidemic of fraud in the subprime industry was highlighted in major reports published jointly by The New York Times and 20/20, by HUD and Treasury, and by The Los Angeles Times. And based on the data likely to have been corrupted by fraud, consider how the rating agencies presumed to slice risk in the MASTR and SASCO deals as finely as cheese at a deli counter.

Glossing Over Prepayment Risk

If you look at the capital structures of enough subprime deals, you’ll soon notice that the unrated, or equity, tranche is almost always smaller than the expected loss. The difference would be made up with interest income earned over the life of the deal. But calculating the net present value of that interest income is a very dicey proposition. By definition, it’s a matter of counting your chickens before they hatch.

With any credit portfolio, the only cash offsetting the credit losses from nonperforming loans is the interest income from the performing loans. And in a mortgage securitization, the total interest income is driven by the rate of prepayment, which is never according to a fixed schedule. Only a tiny minority of homeowners repay their loans over 30 years. Almost all of them prepay when they refinance, when they sell their homes, or when they allow the property to be liquidated in a foreclosure sale. If the loans in a mortgage securitization prepay much faster than originally projected, any shortfall in interest income is lost forever. Again, these deals aren’t like banks, which can book new loans to offset the loans that roll off.

Different investors in the same mortgage securitization have a different sensitivity to prepayment risk, since there’s a predetermined sequence of which investors get repaid first and which get repaid last. This sequence of repayment is called the cash-flow waterfall. The tranches that are hypersensitive to prepayment risk are near the bottom, like those rated triple-B. But they don’t recover principal out of interest income; they get repaid out of excess spread, which is something else altogether. The way the waterfall invariably works, the subordinate tranches do not receive a nickel of principal until after all of the tranches are fully paid on their interest coupon, and after all of the senior tranches are fully repaid on their principal. Whatever is left over is used to cover the credit losses, which are first absorbed by the lowest rated tranches. So a faster-than-expected prepayment rate means that excess spread can be wiped out in a heartbeat.

Another credit truism is that, with any hyperleveraged investment, if some unexpected happens, an investor can get wiped out quickly. That’s what happened in 1999 and 2000, when ratings agencies learned that their subprime models simply didn’t work. A drop in interest rates in 1998 triggered faster-than-expected prepayments on subprime mortgages, and the investors in the most subordinate tranches, which happened to be mortgage lenders, lost their shirts and went out of business. The leader in the subprime industry in the late 1990s was Contifinancial, which issued 12 tranched securitizations, totaling $14 billion, during 1997, 1998 and 1999. Investment grade tranches on all but one of those deals defaulted during the height of the real estate boom, largely because of faster than expected prepayments. Anyone at the agencies who says that the losses on subprime bonds were unforeseeable is feigning amnesia.

Collateralized Debt Obligations: The False Equivalency Between Corporate and Structured Defaults

The scam behind CDOs is simple, or definitional. It’s based on the superficial similarity between CDOs and CBOs or CLOs. Before getting lost in the alphabet soup, let’s clarify the definitions:

CBOs, aka collateralized bond obligations are comprised of corporate bonds;

CLOs, aka collateralized loan obligations, are comprised of corporate loans; and

CDOs, aka collateralized debt obligations, are, in this context, comprised of investments in structured finance entities, most notably residential mortgage bond securitizations.

All three entities are investment portfolios of debt instruments tailored around rating agency claims that they can measure the diversification of credit risk. More specifically, the agencies profess to be able to measure default correlations, the likelihood that, if one bond defaults, a second bond will also default. CDOs are also based on a false equivalency, the notion that a triple-B is a triple-B is a triple-B, that statistically, the risk of default in all triple-B debt obligations increases at the same rate over time . In this alternate universe, the rating defines the reality.

The difference between a corporate bond default and a structured finance default is like the difference between a very sophisticated human being and a very stupid machine. An investment grade corporation is actively managed people who are constantly responding to an ever-changing business environment. A structured deal is supposed to operate like a dumb machine; it never restructures its balance sheet, or spins off nonstrategic assets, or increases the budget for new product development.

Investment grade companies have professional people whose overriding goal is to forestall a payment default, which triggers a fairly predictable and rapid chain reaction of events. Once it becomes apparent that a company is insolvent:

1. The, company loses access to short term credit and faces a liquidity crisis, so that

2. The company fails to pay interest and principal at a date certain, triggering a payment default, so

3. The payment default triggers cross defaults on all the other outstanding debt, so

4, Those defaults trigger cross acceleration, so that all the debt is immediately due and payable, so

5. The company is forced to file for bankruptcy, so that

6. Everyone waits until a bankruptcy judge determines what the creditors will eventually recover.

In a residential mortgage securitization, no one is actively working to forestall the possibility of a default. And once it becomes apparent that some tranches will lose money, nothing happens, since everything has been predetermined by the cash-flow waterfall. And since there’s no fixed obligation to pay principal for 30 years, it may be several years before any payment default actually takes place. (Which is why the rating agencies are not forced to rush and announce a downgrade.) But eventual recovery is determined by the legal structure, not the bankruptcy court.

This is very obvious to anyone who has observed structured finance defaults over time. And that’s why all these CDOs were conceived under a bogus premise, which equated corporate defaults with structured defaults.

CDOs: Bogus Default Correlations

If you buy a newly-rated triple-B corporate bond, the likelihood of default, over 10 years, is supposed to be about 5% But if you hold 100 triple-B bonds, what is the likelihood that more than five of them will default? If you toss a coin 100 times, you can calculate the odds that, say, 75 of the results will be “heads,” because the result of each coin toss is totally uncorrelated to all others. But with different types of corporate bonds, the risk of default may or may not be correlated. Moody’s came up with a way to measure that default correlation. It came up with the concept of a diversity score based on a methodology called the binomial expansion technique. It assumes that the greater the diversification among 30 different industry sectors, the lower the default correlation. All well and good.

But what about structured deals, most notably, residential mortgage securitizations? Moody’s assumed that these bonds would deteriorate at the same rate at the corporate bonds and it initially used default correlations that were pulled out of thin air, or as Dr. Gary Witt quoted the original author of a seminal Moody’s publication, “We just made them up.” Later, Moody’s came up with other default correlations, based on its history of downgrading mortgage deals during the bubble. Needless to say, those correlations had nothing to do with real life. Aside from a few regulated financial entities, there are no triple-B corporate bonds that are deeply subordinated to 20 times leverage at a business with a vacuum of leadership. The subprime collapse of the late 1990s demonstrated a very strong default correlation among hyper-leveraged companies in the mortgage business.

2. Our ratings on structured deals are merely opinions, protected by the 1st Amendment.

“Credit rating agencies are not gatekeepers. Rating agencies are credit market commentators.” Ray McDaniel, Moody’s

Credit ratings are never just opinions, like movie reviews or analyses published by the financial press. They are approbations, more akin to those awarded by the FDA to over-the-counter medications, or like those awarded by health inspectors to public restaurants. They are not guarantees of performance, but they are certifications based on an institutionalized vetting process. But with structured finance deals, they are something much more.

When a rating is awarded to a corporation, the two are clearly separate. The company had an existence that predated the rating. The opposite is true of a structured deal. All of these toxic structured deals were designed at their inception according to specific standards set by the rating agencies. Without their credit ratings, these would never have been created. This is especially true of CDOs, which are designed about credit ratings, not around cash flows. Consider Squared CDO 2007-1, Ltd., a J.P. Morgan deal that closed in May 2007. Upon completion of the ramp up period for acquiring assets, the deal would be forced to liquidate unless Moody’s had confirmed the CDO ratings, which depended on compliance with, among other things, the “Moody’s Asset Correlation Test,” the “Moody’s Minimum Weighted Average Recovery Rate Test,” and the “Moody’s Minimum Weighted Average Recovery Rate Test.” Again, there are hundreds of other deals just like Squared CDO 2007-1, which happens to be one of the notorious Magnatar deals, which were all secretly designed to fail by a hedge fund.

Read the initial ratings “commentary” on Squared CDO 2007-1, and you’ll notice that, like hundreds of other CDO ratings announcements, it reveals nothing that would enable an outside reader to form an independent judgement.

3. We downgraded these mortgage securities on a timely basis.

“We took rating actions as soon as warranted by actual performance data.” Nicolas Weill, Moody’s

At what point should a mortgage securitization be downgraded? It’s hard to say. But it’s easy to identify the point in time when a downgrade is overdue. Whenever, within the first two years, the total loans in foreclosure exceed the dollar amount of the subinvestment grade tranches, some of the investment grade tranches need to be downgraded. At that point there’s no need to wait and see might happen, because it happened already. The cushion to protect those investment grade tranches from credit losses–the excess collateralization and the excess spread– has been irreparably damaged. At that point the triple-B tranches have not yet lost their principal; but there was no way that anyone could argue that they were still investment grade.

And while there may not have been absolute certainty that the triple-B tranches would not lose their principal, the same way there is no absolute certainty that the Republicans will carry Idaho in 2012, the odds of a loss are pretty overwhelming. Because of the way these cash waterfalls are set up, the senior tranches get their principal repaid from the good loans in the pool, and the subordinate tranches get repaid from the bad loans. And each month during 2006, home prices were falling and delinquencies were rising, which was an acid test that things would not get better for years.

So consider, for example, a $2.75 billion subprime deal called Argent Securities Inc. 2005-W2. The deal closed in September 2005, with $135 in capitalization subordinate to the tranche rated Baa3 by Moody’s. And a year later, by October 2006, a total of $135 million in loans were in foreclosure, were classified as “real estate owned'” or were written off. There was no excuse to wait until October 2006 to announce a downgrade; and the deal should have been put on credit watch months earlier. But Moody’s waited another 18 months before it issued its first downgrade in April 2008. By then, about $315 million in loans were in foreclosure or worse.

Or consider Morgan Stanley ABS Capital I Trust 2005-HE5 , which closed in October 2005. The $1.5 billion deal had $63 million in sub-investment grade capitalization, and by November 2006, $63 million in loans were in foreclosure or worse. So by then, a downgrade was overdue. But the deal was not downgraded by Moody’s until April 2008, when the deal had almost $180 million in loans in foreclosure. And once again, there are hundreds of other deals just like these two, which that, by any standard, were neither downgraded nor put on credit watch for at least a year after the need for a downgrade had become certain.

The foregoing only scratches the surface. It does not cover the issues of corporate governance reported by insiders. But it should help you avoid getting sidetracked. Good luck!