Insider's Game

Selected writings by David Fiderer

Goldman’s Blueprint for Dumping Toxic Assets: How These CDOs Were Designed to Fail

First published in The Huffington Post on April 18, 2010

“Although Goldman Sachs held various positions in residential mortgage-related products in 2007, our short positions were not a ‘bet against our clients.'”

That claim, from Goldman’s letter to its shareholders, is easily refuted. The S.E.C. has brought fraud charges on one of Goldman deals known as synthetic subprime mezzanine collateralized debt obligations, or CDOs. While most of these deals remain shrouded in secrecy, one of them, Anderson Mezzanine Funding 2007, Ltd. lays out its blueprint in sufficient detail so that we can pinpoint how and why this transaction’s failure was never in doubt.

When the deal closed on March 20, 2007, there was virtual certainty that investors would get wiped out and that Goldman would receive a windfall. And that’s exactly how things turned out. By December 2009, Anderson Mezzanine’s nominal value had shrunk by more than two-thirds, from $307 million to $94 million, though remaining assets’ fair market value was far less. The investment portfolio, which held only two performing assets, had an average credit rating of CC.

Anderson Mezzanine is by no means unique. More than $70 billion worth of toxic assets were dumped into mezzanine CDOs during an eight-month period between September 2006 and April 2007, when it became obvious to Wall Street banks that the lower-rated slices, or tranches, of mortgage-backed bonds were worthless. Other Goldman deals–Hudson Mezzanine Funding I and Hudson Mezzanine Funding II, various Abacus deals–were also designed to insulate the banks from losses on assets it knew to be worthless.

Eventually The Risk of Failure Morphs Into Absolute Certainty

A CDO is like a mutual fund or a hedge fund. It’s an investment portfolio, which, subject to certain limitations, may be actively managed. Sometimes a CDO, including Anderson, also acts like an insurance company. It receives fees for insuring certain identifiable risks, and, whenever called upon to pay out on an insured claim, it will liquidate part of the investment portfolio.

But insurance companies take on risks when the outcome is in doubt. Anderson Mezzanine was more like a life insurance company that insured the lives of 61 patients with Stage IV lung cancer. Whenever a patient died, Goldman, the insured beneficiary for all 61 patients, would collect $5 million. If Anderson had insufficient cash on hand, Goldman could dip into CDO’s investment portfolio and decide which asset it wanted to liquidate. If the asset could not be sold easily, Goldman would arrange an auction, in which Goldman might end up as the winning bidder.

Cynics might argue that these arrangements smack of fraud and abusive self-dealing, but Goldman could rightfully point to documents that put investors on notice. All of these pitfalls were identified in writing.

Playing the Ratings Game

But these pitfalls weren’t exactly conspicuous. A potential investor would need to spend a lot of time and effort deciphering the offering circular and related documents, such as the Bond Indenture, the Liquidation Agency Agreement, or the Forward Purchase Agreement, in order to figure out what was really going on. He would also need to conduct a financial analysis of the 61 different mortgage securities being insured via credit default swaps.

Or he might take some shortcuts, and simply rely on the deal’s stellar ratings. The most senior tranches of the CDO, comprising 70% of the capital structure, were rated AAA. After all, the rating agencies had reviewed and rated all of the 61 insured mortgage bonds, so their institutional memory and expertise was embedded inside the ratings awarded the Anderson deal.

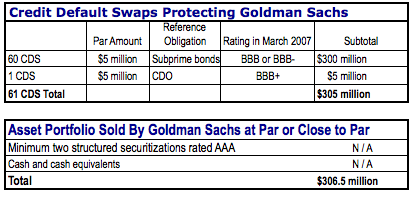

Anderson Mezzanine’s structure, its business model, was defined by credit ratings. Its investments, which were all acquired from Goldman at par or close to par, were all rated AAA. The 61 mortgage securities covered by credit default swaps were rated BBB or BBB-, except for one CDO, which was rated BBB+. If any of those insured mortgage securities were ever downgraded to CCC, Anderson was required to pay Goldman $5 million, the par value of the investment, in exchange for Goldman’s delivery of the underlying mortgage security. Again, this risk of downgrade was part of the institutional knowledge that Moody’s, Standard & Poor’s and Fitch brought to their ratings decisions on Anderson.

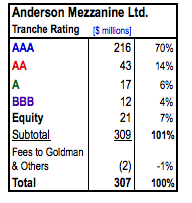

Sixty-one credit default swaps, each for $5 million, total $305 million in contingent liabilities. Those obligations were backed up by cash and investments totaling $306.5 million at closing. (Investors contributed about $308.5 million, from which Goldman and others took out $2 million in fees.) At first blush, the setup seemed like it afforded scant margin for error, given that the AAA investment portfolio was less than 1% larger than the credit default swap obligations. But investors could take comfort in the fact that Goldman had skin in the game. The bottom 10% of the capital structure–$21 million in equity plus $10 million in bonds rated BBB–would be funded by Goldman itself. The other 90% of the deal was marketed to outsiders, who bought tranches in the deal rated AAA, AA and A.

Insuring Assets For 30% More Than Their Mark-to-Market Value

For Goldman, $31 million spent on equity and BBB bonds was the cost of putting the deal together. Given the market value of the securities being insured, Goldman got a big windfall on day one. On March 20, 2007, the market value of the mortgage securities was about 70% of par, or 70 cents on the dollar. Since the beginning of 2006, the valuations of subprime mortgage securities had been benchmarked against a market index known as the ABX. The BBB tranche of the ABX had not traded at par since November 2006. At the end of March 2007, the BBB and BBB- tranches of the ABX traded in the range of around 70.

Goldman was not the only Wall Street insider that invested in CDOs designed to produce windfalls. Other hedge funds, Magnetar and Paulson & Co., did the exact same thing.

Accountants would have picked up on the problem right away. Under the new accounting rules, exotic instruments like Anderson Mezzanine were required to be measured according their fair value. Since there was very little trading of subprime securitizations, the FASB specifically directed that the ABX be used as a proxy to ascertain fair value. For better or worse, accounting rules could have mandated that investors recognize an instant 30% loss, based on the fair value of the 61 assets insured via credit default swaps.

Chronicles of Defaults Foretold

But accountants usually wait to receive the financial statements before conducting any review. The wait for Anderson’s statements was exceptionally long. The first financial statement was issued on July 12, 2007, well after most companies had closed their books for the first and second calendar quarters. As it happened, July 12, 2007 was the first date that one of Anderson’s credit default swaps became due and payable. On July 12, 2007, Standard & Poor’s downgraded Argent Securities Trust 2006-W4 M-9 from BBB to CCC.

The downgrade was no surprise. In fact, it was amazing that the bonds had not been downgraded much earlier. Long before the Anderson deal closed, it was obvious that the Argent bonds were worthless. In February 2007, Argent 2006-W4 had attained a foreclosure rate of 9%. For any mortgage deal, a 9% foreclosure rate in the first year is astronomical, literally off the charts. By the time of the S&P downgrade in July, the foreclosure rate had spiked to 11%.

Consider that it takes quite a while before a residential property is foreclosed upon. In general, the foreclosure process cannot begin unless a borrower has been delinquent in his payments for at least four months. The process of resolving a loan default–from the date of initial delinquency, to the date when foreclosure proceedings commence, to the date when final sale proceeds are applied against the loan balance to calculate the true loss–can take about a year. That’s why Moody’s rule of thumb, for evaluating a pool of mortgages, was to assume that only 3% of the losses were incurred in the first year.

It’s worth remembering that all of these insured mortgage bonds were comprised of 30-year, and sometimes 40-year, loans; and a lot of bad things can happen over that timeframe. And subprime loans had all sorts of features that virtually assured a high degree of nonperformance. In many ways, Argent 2006-W4 was a typical subprime securitization, very much like those referenced by the ABX. About 40% of the loans were “stated income” loans, also known, for obvious reasons, as liar loans. About half the loans were “cashouts,” where the borrower increases the size of the loan on his existing home. Cashouts are susceptible to inflated appraisals, since they are not tied to the reality check of an arms length home purchase.

There were other signs that things would play out worse than expected during the weeks preceding the closing date of Anderson Mezzanine. The two largest subprime lenders had suddenly shut down operations. On February 22, HSBC, the largest subprime lender, announced that it was withdrawing form the market, after revealing a stunning $10.5 billion loss. New Century Financial, the second-largest subprime lender, faced a liquidity crisis following its announcement that the firm was the target of a criminal investigation for securities fraud.

New Century was the originator for at least 10 of the 61 mortgage bonds insured by Anderson Mezzanine. The foreclosure rate for a number of the New Century bonds, like that of the Argent bonds, was extraordinarily high. By February 2007, many of the New Century bonds had attained a foreclosure rate that exceeded 5%. [Update April 27, 2010 11:15: Senator Levin’s Committee discerned that New Century was the originator on 25 of the 61 deals.]

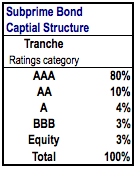

The 5% threshold is important. Any subprime bond with an initial rating of BBB or BBB-, including all the bonds insured by Anderson, is located in the bottom 5% of the capital structure. Subprime bonds, for all their complexity, followed a very standardized cookie cutter capital structure, which was inevitably linked to credit ratings.

Even though large numbers of borrowers had stopped making their monthly mortgage payments, the mortgage bonds were still paying out interest and principal to investors. Within each mortgage bond, the distribution of cash flows may be extraordinarily complex, based on individualized reserve funds, delinquency triggers and default triggers. While some homeowners had stopped paying, other homeowners were prepaying their mortgages, providing sufficient cash to keep all the bond investors current. Still, the business intent behind each of these deals was that the lower-rated tranches, those rated BBB and BBB-, would get wiped out before the higher-rated tranches, representing 95% of the deal, lost a single dollar.

And since more foreclosures were happening sooner than expected, it was inevitable that the bonds rated BBB and BBB- would get wiped out. The capital structures allowed for almost no margin for error. The way the deals were structured, every $100 in debt was backed up by $103 in mortgages. There was a $3 dollar equity cushion. Yet the rating agencies had assumed a 6% credit loss, meaning that every $100 would lose $6 from defaults. How could a $3 equity cushion offset a $6 loss? The idea was that the losses would be spread out over time, say $1 each year, so that interest income earned over subsequent periods would offset future losses from defaults. But if the losses were frontloaded, due to high-than-expected foreclosures in the first year, it quickly becomes obvious that the $3 equity cushion will not insulate the lower-rated tranches from suffering losses.

A 5% foreclosure rate does not translate into 5% in losses. But a 5% foreclosure rate in the first year is a distillation of several other trends–higher-than-expected delinquency rates, foreclosure rates and prepayment rates–that, when taken together, all foretold the inevitability of major losses in the tranches rated BBB and BBB-. Put another way, if a subprime mortgage bond suffered a 5% foreclosure rate in its first year, it didn’t really matter if housing prices stabilized, got better, or got worse. There simply was no way to mathematically construct a plausible scenario where the lower-rated tranches came out whole.

That’s why it was certain by March 2007 that the BBB tranches would get wiped out. Yet, at the time that Anderson Mezzanine closed, all 61 mortgage deals were still rated investment grade. In October 2007, 14 additional subprime bonds were downgraded to CCC and 14 additional credit default swaps became due and payable to Goldman Sachs. In January, an additional 10 downgrades triggered an additional $50 million payable to Goldman.

The Mad Rush to Dump Worthless Assets Into CDOs

Anyone who had done a cursory analysis of the 61 mortgage bonds could see that it was only a matter of time before the bonds would be downgraded, and that they would default. As it happened, Goldman, and the other large investment banks were in a race against time. After HSBC and New Century had announced their disastrous results, Wall Street banks went into overdrive. During March 2007, they sold almost $21 billion worth of mezzanine CDOs, triple February’s volume and a new monthly record.

The rating agencies were swamped. They were asked to review and rate 31 mezzanine CDOs issued during a five-week period, between February 28 and April 5, 2007. “It was a massive volume and we did not have the capacity to handle it,” one rating agency executive confided to me. The agency analysts were certain susceptible to pressure from their Wall Street clients. One noted expert on structured finance and CDOs had spoken of a bank that trained its people how to pressure analysts at the rating agencies to get higher ratings for its CDOs.

Investors in many of the mezzanine CDOs issued during that five-week period have subsequently brought lawsuits alleging fraud on behalf of the underwriting banks, and, in some instances, the rating agencies as well.

Anderson’s Declining Asset Portfolio

Anderson Mezzanine assumed two kinds of credit risks. There was the risk that 61 mortgage securities would fail, or at least be downgraded to CCC. There was also the risk that the structured securities held in Anderson’s investment portfolio would either default or, if ever liquidated, sell at a discount. Unlike the 61 credit default swaps, we cannot identify the investments, specially selected by Goldman, which were acquired by Anderson. We know of a few investment criteria. All of the newly acquired assets were to be rated AAA. All of the investments were to be structured securitizations, holding pieces of loans in residential real estate, commercial real estate, or some other structured deal with an insurance guaranty. No more than 12.5% of the portfolio could be in CDOs. Though the 61 credit default swaps obligations were fixed at closing, substitutions were allowed within the AAA investment portfolio.

The structure made no pretense of risk diversification. The minimum number of investments in the AAA portfolio was two. Or rather, no more than 50% of the investments could have indirect exposure to a single issuer of mortgage securities, a single mortgage servicer, or a single swap counterparty.

Though we cannot identify Anderson’s AAA holdings, we do know that that by July 2007, when Anderson’s investors received their first monthly statement, market prices for structured mortgage deals were beginning to collapse. As more credit default swaps became payable, with CCC downgrades announced in October 2007, January 2008 and later, the market prices of all structured real estate deals kept declining.

Nominally, whenever a credit default swap became due and payable to Goldman, Anderson did not hand over $5 million in exchange for nothing. These were physical delivery swaps, meaning that Goldman would exchange a mortgage bond, which once had a par value of $5 million, in exchange for $5 million in cash. Now presumably, Anderson’s newly acquired mortgage bond had some value, albeit a small fraction of the original $5 million. Anderson was required to sell that distressed bond in the marketplace. The party in charge of selling that distressed bond was Goldman Sachs, though it could take its sweet time about. Goldman had a one-year deadline for closing the sale.

On June 12, 2009, Anderson Mezzanine alerted investors that there was insufficient cash to make deb service on behalf investors in the tranche initially rated AA. But those investors had been disabused of any hope of getting their money back at a much earlier date.