Insider's Game

Selected writings by David Fiderer

The Times Story On Goldman’s Role in AIG’s Downfall Is More Damning When Placed In Context

First published in The Huffington Post on February 8, 2010

Placed in a broader context, the front page story in The New York Times is even more damning of Goldman Sachs than readers might realize. Goldman played an active role in the destruction of AIG. During Hank Paulson’s tenure as the firm’s CEO, Goldman engaged in a series of sham transactions designed to give the false impression that it was buying credit default swaps as an instrument for risk management. In fact, it acquired those swaps in order to double down on bets against collateralized debt obligations, or CDOs, which it knew to be fatally flawed. In the latter part of 2008, Paulson and his proxies maneuvered AIG into a liquidity crisis in order to protect Goldman at the expense of the U.S. taxpayer.

To appreciate how the Times piece fits into a larger picture, you need to understand why these CDOs were so obviously toxic.

The Fatal Flaw Of These CDOs

AIG went bust because it sold credit default swaps for CDOs stuffed with slices of subprime mortgage bonds. Those subprime mortgage bonds all had remarkably similar capitalization structures, divided among different classes, or tranches, of seniority. The top 80% in seniority had a credit rating of AAA. The bottom 10% was rated A and below.

The bottom 10% was especially vulnerable because of something that was an open secret at the time. The subprime mortgage market was riddled with fraud. So the data used by Goldman and others to structure these bond deals was highly suspect.

Who bought the bottom 10% of these subprime bond deals? A lot of those lower-rated tranches were not sold directly to investors. Rather they were stuffed into CDOs. This point is critical. These CDOs were not comprised of mortgage loans, or even slices of mortgage loans. Rather, they held deeply subordinated claims on risky subprime mortgages. Because these tranches were the last ones to get repaid, it was easy to foresee, at the time these CDOs were put together, that investors would lose significant amounts of principal.

People marketing these CDOs claimed that they were safe, because the risks were diversified, and because of excess collateral cover. But that line of reasoning never made any sense. The lower rated tranches were like the passengers in steerage on the Titanic. Once the ship starting sinking, those passengers were the last ones given access to the lifeboats. As soon as the housing market started sinking, those lower-rated tranches would be the last ones given access to any foreclosure proceeds.

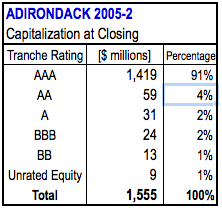

AIG thought it was selling credit protection for AAA risk. And in fact, these CDOs, like subprime mortgage bonds, were tranched in a way that made them top heavy with AAA ratings. Consider, for example, forAdirondack 2005-2, a CDO arranged by Goldman, which “sold” almost all of the AAA tranche Societe Generale, which in turn bought credit protection from AIG. Of Adirondack 2’s $1.55 billion capitalization, $1.42 billion, or 91%, was rated AAA.

So how could anyone get comfortable with the notion that 90% of a portfolio, heavily weighted with deeply subordinated claims on risky mortgages that were likely to be infected with fraud, represented a AAA-quality credit risk? It’s a question for which there is no good answer. If anyone looking at these deals had done proper due diligence and done a common-sense analysis of the structural risks, he would have realized three things:

1. The original credit ratings for lower-rated slices of these subprime bond deals were meaningless;

2. The original credit ratings on these CDOs were even more meaningless; and

3. The CDOs were destined in fail in a big and obvious way.

Goldman’s Malign Intent

Obviously, the people at AIG never figured out what was going on until it was too late. But there’s a mountain of circumstantial evidence that the people at Goldman had a keen grasp of the fatal flaws of these CDOs, which they structured. The Times piece is a major addition to that mountain of evidence:

[Former AIG executive Alan] Frost cut many of his deals with two Goldman traders, Jonathan Egol and Ram Sundaram, who had negative views of the housing market. They had made A.I.G. a central part of some of their trading strategies.

Mr. Egol structured a group of deals — known as Abacus — so that Goldman could benefit from a housing collapse. Many of them were actually packages of A.I.G. insurance written against mortgage bonds, indicating that Mr. Egol and Goldman believed that A.I.G. would have to make large payments if the housing market ran aground. About $5.5 billion of Mr. Egol’s deals still sat on A.I.G.’s books when the insurer was bailed out.

“Al probably did not know it, but he was working with the bears of Goldman,” a former Goldman salesman, who requested anonymity so he would not jeopardize his business relationships, said of Mr. Frost. “He was signing A.I.G. up to insure trades made by people with really very negative views” of the housing market.

As further evidence that Goldman used AIG to profit by shorting CDOs, rather than to manage its preexisting risk exposure:

[N]egotiating with Goldman to void the A.I.G. insurance was especially difficult, Federal Reserve Board documents show, because the firm did not own the underlying bonds. As a result, Goldman had little incentive to compromise.

Most importantly, the government never purchased the Abacus deals when it bought $62.1 billion other CDOs at par, back in November 2008. Why didn’t the parties feel a need to take the Abacus deals off of AIG’s balance sheet? It’s an extremely important question, for which we will not have an adequate answer until we see the actual documentation, specifically: the offering memoranda, the performance reports and swap agreements.

Hiding Behind Societe Generale

The Times story also suggests that Goldman used Societe Generale as a front, to conceal from Frost and others the size of their cumulative bet against these CDOs:

Through Societe Generale, Goldman was also able to buy more insurance on mortgage securities from A.I.G., according to a former A.I.G. executive with direct knowledge of the deals. A spokesman for Societe Generale declined to comment.

It is unclear how much Goldman bought through the French bank, but A.I.G. documents show that Goldman was involved in pricing half of Societe Generale’s $18.6 billion in trades with A.I.G. and that the insurer’s executives believed that Goldman pressed Societe Generale to also demand payments…On Nov. 1, 2007, for example, an e-mail message from Mr. Cassano, the head of A.I.G. Financial Products, to Elias Habayeb, an A.I.G. accounting executive, said that a payment demand from Societe Generale had been “spurred by GS calling them.”

As noted earlier in the story:

In addition, according to two people with knowledge of the positions, a portion of the $11 billion in taxpayer money that went to Societe Generale, a French bank that traded with A.I.G., was subsequently transferred to Goldman under a deal the two banks had struck.

The AAA Pyramid Scheme Embedded Inside AIG

The Times reports that Goldman tailored the terms of the swaps to exploit these defective credit ratings:

Here’s an example of how terminology for a general news readership can lead to confusion. In the context of the story, the Times seems to be referencing the ratings of the CDOs, not the subprime bonds held by the CDOs. The distinction is critical because almost all subprime bonds were downgraded in 2007, whereas most of these CDOs were not downgraded prior to May 2008, when they received minor downgrades.

Most importantly, almost all these CDO tranches were rated AAA during November 2007, when, as theTimes reports, Goldman was demanding billions in cash collateral. There is no way to reconcile a 40% diminution of value, which Goldman repeatedly asserted, with a AAA rating. It’s like saying 2 + 2 = 11. In effect, Goldman was admitting that the CDOs’ ratings were a joke.

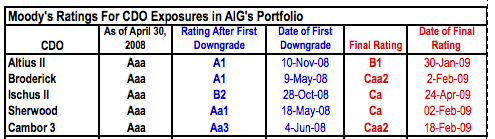

It was an especially cruel joke on AIG and on the American taxpayer. If the ratings agencies had severely downgraded the CDOs in 2007 or earlier in 2008, AIG’s day of reckoning would have come sooner. Instead, that day coincided with Lehman’s bankruptcy. The ratings agencies announced their major downgrades of AIG after the close of business on September 15, 2008. Those downgrades triggered cash collateral calls and on AIG on September 16, 2008, the same day that a money market fund, which wrote down Lehman paper, broke the buck and triggered widespread panic in the money markets.

As noted before, the timing of the CDO downgrades looks suspicious. Eric Kolchinsky, a former managing director at Moody’s, has alleged that the ratings agency deliberately and deceitfully delayed the announcements of downgrades of various CDOs. The House Oversight Committee is still investigating the matter.

Why Goldman Pressured AIG to Hand Over Cash

The thrust of the front-page Times article was that Goldman aggressively pressured AIG to hand over cash collateral beginning in 2007, Goldman asserted, because, the CDOs “were deemed to have lost value.” But negotiations were always at an impasse, for an obvious reason. There was no way to settle on agreed-upon “market value” for the CDOs. These securities weren’t bought or sold, like Treasuries or shares of IBM. Nor was there any market benchmark upon which the CDOs could be valued. The only way to set a price, according to auditors for AIG and the Federal Reserve, was according to internal valuation models.

The Times reports:

The Times reporting suggests that Goldman wanted to control the dispute by using a nominally independent third party, PricewaterhouseCoopers, which had shifted into Goldman’s camp:

Pricewaterhouse had supported A.I.G.’s approach to valuing the securities throughout 2007, documents show. But at the end of 2007, the auditor began demanding that A.I.G. provide greater disclosure on the risks in the credit insurance it had written. Pricewaterhouse was expressing concern about the dispute.

The insurer disclosed in year-end regulatory filings that its auditor had found a “material weakness” in financial reporting related to valuations of the insurance, a troubling sign for investors.

Of course, a highly plausible explanation is that Pricewaterhouse, like AIG, had assumed that the CDOs’ AAA ratings were credible, until Goldman set them straight. But again, this gets back to the issue of whether Goldman knew these deals were toxic from the start. Goldman opposed proposals that would have enabled it to make its case to others:

Mr. Sherwood said he did not want to ask other firms to value the securities because “it would be ’embarrassing’ if we brought the market into our disagreement,” according to an e-mail message from Mr. Cassano that described the call.

The Goldman spokesman disputed this account, saying instead that Goldman was willing to consult third parties but could not agree with A.I.G. on the methodology.

The dispute would have been more than embarrassing for Goldman. It would have shed light on the fatal flaws of these CDOs, which, at the time, were not known to the broader financial community. These flaws were not known because so few parties took a serious look at the credit risk, which was largely assumed by a handful of companies: AIG Financial Products (under a guarantee by its parent) and the monoline insurance companies. In early 2008, the monolines started settling their contingent CDO obligations for a fraction of par. As noted earlier, they were able to do so because they had the backing of their regulators. AIGFP, which was unregulated, was on its own. Ever prescient, Goldman never bought credit protection from the monolines.

Goldman did not “own” the cash it held. Rather, the cash represented margin that could, in theory, be returned to AIG if the CDOs’ value rose again. Of course, in reality, if you hold the cash you have the upper hand in any negotiation. Also, the way structured finance deals work, if early credit losses are worse than expected, the diminution of value is permanent. The other borrowers in the pool, who never pay more than 100% of their principal and interest, won’t make up the difference. Finally, as noted before, the cash collateral for derivatives, like credit default swaps, is very different than the cash collateral for a loan or other obligation. Goldman’s claims had preferred treatment, another reason why, once it got its hands on the cash, it held the upper hand in any negotiation.

How Hank Paulson Used Proxies to Rig the Eventual Outcome

One thing is as certain as death and taxes. During 2007 and 2008 Edward Liddy was repeatedly briefed, at length, by Pricewaterhouse and by senior management at Goldman, about the firm’s CDO exposure with AIG and about the valuation dispute. If the matter was so important that Goldman’s CFO and vice chairman took an active role in negotiating the circumstances for simply attempting to resolve the dispute, then Ed Liddy thoroughly understood the matter and the stakes that were involved. This will all come out when Liddy’s briefing books, and other related documentation and correspondence, are obtained by the House Oversight Committee, which is investigating this matter.

Liddy was the Chairman of the Audit Committee on Goldman’s Board of Directors. Every audit committee of the board of every publicly held financial institution is briefed in depth about risk concentrations at the firm. There is no way that Pricewaterhouse would leave itself exposed by not thoroughly briefing Liddy about these matters. While it may be a part-time obligation, being Chair of the Audit Committee at Goldman is a very important job. And during one all-important week, Liddy did some moonlighting.

A few minutes after he spoke with Goldman’s CEO, Lloyd Blankfein, on September 16, 2008, and shortly after he first considered a government bailout of AIG, Hank Paulson unilaterally decided that Liddy should immediately become AIG’s new CEO. Unlike Liddy, AIG’s CEO at the time, Bob Willumstad, had relatively clean hands in the CDO saga. Willumstad had been part of AIG’s management for about three months, and had joined the AIG board in April 2006, when most of Goldman’s toxic CDOs had already been insured by AIG.

That same afternoon, Liddy was on a plane to New York, to start at AIG the next day. Liddy was officially made CEO and Chairman of AIG on September 18. And of course, he immediately immersed himself into negotiating the terms of the government bailout facility, which he signed on September 22. Only on the following day, on September 23, 2008, that Liddy chose to make his resignation from Goldman’s board effective.

That was also the week when Paulson spoke to Blankfein 24 times by phone. For further clarification at to why it an innocent explanation of all this is beyond any realm of plausibility, see this earlier piece.

“Who the heck is Dan Jester?” asked Times Opinionator columnist William D. Cohen, who answered his own question last week. Jester was the former Goldman deputy CFO who was plucked by Treasury Secretary Paulson in the summer of 2008 to act as his “contractor,” i.e. someone for whom usual formalities pertaining to government accountability would not apply. But Tim Geithner made more calls to Jester, during the fall of 2008, than to any other bona fide Treasury employee, with the exception of Hank Paulson. Cohen writes:

One of the shots being called during that period was the decision for AIG to hand over $18.7 billion in scarce cash to the CDO counterparties in exchange for zero concessions.

There are many people who do not know how to speak forcefully and effectively to the rating agencies, but that group would not include a former deputy CFO from Goldman. It would be somewhat analogous to Katie Couric getting flustered when asked to read a teleprompter. There is no way that the agencies could have been aware of AIG’s difficulties and not have been equally aware of their own role in contributing to those difficulties. Nor could they have been unaware that a downgrade would trigger AIG’s liquidity crisis. On the same day that the markets were absorbing the shock from the Lehman bankruptcy, if the government asks the agencies to wait just a bit longer to see how the evolving situation plays out with regard to delicate negotiations for a private bank deal to provide new liquidity for AIG, the agencies would ordinarily be inclined to pause for a bit.

For those and other reasons, I believe Jester’s feeble performance was deliberate, that the endgame was to trigger a liquidity crisis at AIG in order to force a government bailout, which would be a backdoor bailout of Goldman. The House Oversight Committee should review Jester’s public and private emails and phone records to get more clarity on this point.

As Paulson wrote in his new book, “Much of my work was done on the phone, but there is no official record of many of the calls. My phone log has many inaccuracies and omissions.” Why would the electronic records of his phone calls be inaccurate, or have any omissions? It’s the sort of disclaimer Dick Cheney would give.