Insider's Game

Selected writings by David Fiderer

Hank Paulson Rewrites History Before Congress

First published in Huffington Post on May 25, 2011

Hank Paulson could not keep his story straight during his nonstop dissembling session before Congress. When asked why the government did not step in to avert a Lehman Brothers bankruptcy, Paulson said, “We were unable to find any buyer to come in and make the acquisition on an assisted basis or an unassisted basis.”

That particular whopper stood out, and was quickly corrected. “Did Bank of America request your assistance to purchase Lehman?” asked Rep. Mike Quigley, D-Ill.

Paulson pivoted, but kept contradicting himself. “We went to Bank America repeatedly,’ he said, “and Bank America asked each time for more assistance and we had the — we had the private sector ready to fill the gap. But Bank America in my judgment was never serious about it, because each time they showed less interest. And it turns out they were interested in Merrill Lynch.”

His story, involving repeated discussions about a transaction with government assistance, doesn’t jive with his earlier version of events. “I never once considered it appropriate to put taxpayer money on the line in resolving Lehman Brothers,” he said the day Lehman filed for bankruptcy. Ten months later, he claims, “If Tim Geithner, Ben Bernanke and Hank Paulson had found something legal we could have done to save Lehman, we would have.”

Fortune reported a different story. BofA’s CEO Ken Lewis said he would acquire Lehman so long as the government would take over $65 billion of troubled real estate loans off of Lehman’s books. That was more than twice the $29 billion secured loan the Fed had made to JPMorgan as part of the Bear Stearns takeover, but the amount also reflected the subsequent deterioration in mortgage securities. When Bear Stearns was taken over in March 2008, the AAA tranche of the ABX index for subprime mortgage securities was still selling at close to par; by September 2008, its value had fallen by cose to 20%, and the lower-rated ABX tranches were trading at pennies on the dollar. So Paulson decided there would be no further discussions that involved a government-aided takeover of Lehman.

Barclays also tried to negotiate a deal to take over Lehman, which our government’s unwillingness to help seemed to kill that effort. On Sunday, September 14, 2008, Britain’s Financial Services Administration, “concluded based on the amount of diligence, the risk profile, and the lack of any assistance from the U.S. that they were not going to let it proceed.” [Emphasis added.]

Later that same Sunday, the U.S. government announced that it would help out all investment banks except for Lehman:

First came a tantalizing ray of hope with the word that the Federal Reserve Board agreed to expand the collateral that investment banks could pledge to the Fed as part of both the Primary Dealer Credit Facility – the name given to the historic measure that allowed investment banks to borrow directly from the Fed window after the demise of Bear Stearns on March 16 – and the Term Securities Lending Facility, a $70 billion “collateralized borrowing facility” created on Sunday by banks to enhance liquidity in the marketplace.

When the Lehman executives started to hear on Sunday afternoon that these windows of emergency financing were opening up, they called the New York Fed to see if it were true. If the Fed allowed Lehman to pledge its shaky collateral to the discount window “we might get a reprieve,” one Lehman banker said. But the Fed told Lehman, according to this Lehman banker, “‘Yeah, we’re doing that for everybody else but you. We’re going to let you guys go.'”

Paulson’s spin that, “it turns out they [Bank of America] were interested in Merrill Lynch,” is, to put it charitably, disingenuous. The specter of a Lehman bankruptcy was the only reason that Merrill considered a BofA takeover. In his sworn testimony, Merrill CEO John Thain said that the only reason he initiated talks with Bank of America was because he was concerned that Merrill would face a liquidity crunch – not insolvency – following Lehman’s collapse. Sources to The Financial Times claim that Thain only initiated calls to Lewis after Paulson, Thain’s former boss at Goldman, gave “a stern talking to.” Specifically, “These witnesses, who represented different parties in the talks, add that it was only after Mr. Thain returned from his one-on-one with Mr. Paulson, looking somewhat shaken, that he placed the call to Mr. Lewis.”

Merrill’s multibillion dollar losses, which prompted Ken Lewis to reconsider closing the merger, were also traceable to Paulson’s bad faith tactics. The popular media narrative is that Merrill’s losses suddenly became apparent in mid-December 2008, when Lewis contacted Paulson and Bernacke to say he wanted to back out of the deal. In fact, Merrill’s budget plans had assumed that its mark-to-market losses would reverse before year-end. When it became clear that time was running out, Lewis realized that he could not go forward with the deal. As Lewis said in his deposed testimony, “We earlier on had more days on the month so that at least some of the marks would come back, but now we had not very many business days because Christmas was coming and all that. So we became concerned just of the acceleration of the losses.”

When were those mark-to-market losses first become apparent? Mid-November, according to a Fed advisor, whose e-mail to Ben Bernacke said, ” There are clear signs in the data we have that the deterioration at Merrill Lynch has been observably under way over the entire quarter, albeit picking up significantly around mid-November.” Mid-November was when Paulson announced his about-face on using TARP to deal with the collapse in mortgage securities.

The credit market was thrown into turmoil by Henry Paulson’s sudden changes to the $700bn Troubled Assets Relief Programme, announced late on Wednesday…’Paulson has really messed up everything. His news really couldn’t have been worse for financials,’ said a credit trader in New York yesterday…

If the banks were hard hit by the news, the indices that track distressed and mortgage related assets were cratered. “This has really not been good news for ABS and CMBS. It has sold off pretty fast,” said a London credit trader yesterday. The triple-A portion of the ABX dipped below 37 yesterday, a level described by Citibank analysts as “truly shocking.” “Banks count cost of Paulson’s Tarp U-turn’,” EuroWeek, November 14, 2008

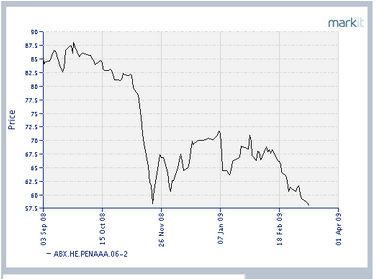

Markit’s ABX HE PENAAA 06-02 index of first lien subprime mortgages is a typical benchmark for valuing all sorts of mortgage investments similar to those held by Merrill.

Notice how the slope of the line becomes almost vertical by mid-November. The decline in value between November 3 and November 20 was 29%. This kind of precipitous free-fall, among the very safest tranches within this type of AAA-rated securities, was unprecedented. Declines of similar magnitudes were seen in all for types of mortgage securities, such as the CMBX index for commercial properties.

After November 20, benchmark prices started shooting upward, reflecting an unprecedented level of price volatility. Nobody felt very confident about measuring the true economic value of these mortgage instruments, and BofA was apparently hoping for a year-end price recovery.

The fallout of Paulson’s two disastrous decisions — to let Lehman fail and reverse his position on foreclosure relief — prompted the former Treasury Secretary to abuse his powers further, with some not-so-veiled threats. He threatened Lewis, telling him not to back out of the Merrill deal, not to renegotiate the terms, and not to disclose the problems until after the deal closed. Paulson concealed the situation from the SEC, the Office of Currency Control and the TARP Oversight Panel. After the fact, Paulson tried to place the blame on the Fed. In his prepared statement, Paulson writes:

Some have suggested that there was something inappropriate about my conversation of December 21st with Mr. Lewis in which I mentioned the possibility that the Federal Reserve could remove management and the board of Bank of America if the bank invoked the MAC [material adverse change] clause.

Except no one at the Fed recalls ever suggesting any such thing. When Rep. Dan Burton, R-Ind., challenged him, Paulson explained, “I do not know whether someone in those conversations or calls expressly said it or if my understanding came from just the tone and the forcefulness.” The exchange below is typical of how congressmen struggled to get a straight answer out of the former treasury secretary:

BURTON: First of all, I asked Mr. Bernanke if he talked to you about telling Mr. Lewis if they used the MAC clause, that they were going to be fired. And he said he didn’t give you any instruction or say anything to you about that.

And yet when you spoke, you said that — in — in your testimony, you said you were confident that that was a strong opinion of the Federal Reserve. How did you know that?

I mean, there must have been some communication. How did you know that — that you were confident that was their position?

PAULSON: Well, I — I would say two things they are. First of all, you’re right that I do not remember been Bernanke ever suggesting to me that the Fed…

BURTON: You don’t remember.

PAULSON: The — the…

BURTON: You know, Mr. Bernanke said the same thing. He said he didn’t remember.

PAULSON: But — but what I — what I do — so you asked where I came away with that — with that view.

BURTON: Yes.

PAULSON: And I participated in a number of meetings and calls where Chairman Bernanke participated. There were lawyers from the Fed, staff members from the Fed, people from Treasury. And I came away from that — those calls — with that understanding.

BURTON: Well, who’s — wait a minute. Wait. You came away from that, from those phone calls…

PAULSON: Let me just — let me just…

BURTON: Well, no, listen. Just a second. If you came away from that — from those phone calls — somebody must have said, “Hey, we can’t let them do this.”

PAULSON: Well, I just…

BURTON: And I would suggest that it might have been Mr. Bernanke.

PAULSON: Well, what — what I would say to you — I do not know whether someone in those conversations or calls expressly said it or if my understanding came from just the tone and the forcefulness.

BURTON: You know, you’re a very smart man. I don’t think anybody’s buying what you’re saying right now. I mean, you — you guys were on a phone call. There was a number of conversations and e- mails, and you’re saying that you didn’t get any — any suggestion from Mr. Bernanke that — that he wanted you to let them know they were going to be fired, if they didn’t do what you said.

PAULSON: I — I said I clearly came away with the understanding that this committee has, which was substantiated by the e-mails that have been released and some of the other things, that that was the view of the Fed. But I — I also don’t remember Ben Bernanke ever — ever talking about that possibility with me.

BURTON: It’s interesting that both you and Mr. Bernanke can’t remember.