Insider's Game

Selected writings by David Fiderer

How An FCIC Commissioner Fabricated a 25-Million Mortgage “Meltdown”

First published in OpEdNews on January 14, 2011

How do Fannie and Freddie’s loans compare to the rest of the market? They perform a lot better, with serious delinquency rates about one-half that of all mortgages nationwide. (The Mortgage Bankers Association defines serious delinquencies as 90 days or more delinquent, or in the process of foreclosure.) The chart from the Federal Housing Finance Agency shows that the industry’s rate of serious delinquencies was 8.7%; for government-sponsored enterprises it was 4.3%.

If you drill down further, and focus on the small segment of GSE loans to borrowers with FICO scores below 660, the serious delinquency rate is worse than the MBA average, but not by a lot. Subprime loans perform exponentially worse. A mountain of data debunks the rightwing myth that the GSEs led the race to the bottom in mortgage lending standards.

Why the disparity? Consider the different business models. Fannie and Freddie saw mortgage loans as buy-and-hold propositions. So they were more motivated to take steps to limit fraud. Wall Street took a different approach with its originate-to-distribute model. None of the gatekeepers in the distribution chain–the mortgage brokers, the nonbank lenders, the rating agencies, the Wall Street banks–ever intended to retain the credit risk, so they had scant motivation to limit fraud.

Fabricating A Story About Fannie And Freddie To Distract Away From Fraud

As evidenced by their “primer,” GOP members of the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission are desperately seeking to preempt the issue of fraud. They purport to deliver a document to “reflect the clear intention of” the Fraud Enforcement and Recovery Act of 2009, they but defy the clear intention of the Act , which was to produce document that would “specifically [examine] the role of…fraud and abuse in the financial sector, including fraud and abuse towards consumers in the mortgage sector.” The GOP “primer” banished the words “fraud” and “enforcement” from its text, along with the words “Wall Street,” “shadow banking,” “interconnection,” and “deregulation.”

FCIC Commissioner Peter Wallison neatly summarized the disinformation campaign in “Barney Frank, Predatory Lender”:

When the crisis first arose, the left’s explanation was that it was caused by corporate greed, primarily on Wall Street, and by deregulation of the financial system during the Bush administration. The implicit charge was that the financial system was flawed and required broader regulation to keep it out of trouble. As it became clear that there was no financial deregulation during the Bush administration and that the financial crisis was caused by the meltdown of almost 25 million subprime and other nonprime mortgages–almost half of all U.S. mortgages–the narrative changed.

The new villains were the unregulated mortgage brokers who allegedly earned enormous fees through a new form of “predatory” lending–by putting unsuspecting home buyers into subprime mortgages when they could have afforded prime mortgages. This idea underlies the Obama administration’s proposal for a Consumer Financial Protection Agency. The link to the financial crisis–recently emphasized by President Obama–is that these mortgages would not have been made if regulators had been watching those fly-by-night mortgage brokers.

There was always a problem with this theory. Mortgage brokers had to be able to sell their mortgages to someone. They could only produce what those above them in the distribution chain wanted to buy. In other words, they could only respond to demand, not create it themselves. Who wanted these dicey loans? The data shows that the principal buyers were insured banks, government sponsored enterprises (GSEs) such as Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and the FHA–all government agencies or private companies forced to comply with government mandates about mortgage lending. When Fannie and Freddie were finally taken over by the government in 2008, more than 10 million subprime and other weak loans were either on their books or were in mortgage-backed securities they had guaranteed.

That’s a lot of mendacity in three hundred words. Today we’ll focus on the numbers. Wallison’s claim that 25 million loans were already in “meltdown” does not pass the laugh test. Of the 55 million mortgage loans in the United States, the highest number of serious delinquencies was never higher than 5.1 million, according to data compiled by LPS Mortgage Monitor. Of the 30.5 million loans owned or guaranteed by Fannie and Freddie, no more than 1.5 million were ever seriously delinquent (using the MBA definition). Though millions of other mortgages may be at risk because of negative equity and other reasons, Wallison’s “meltdown” characterization existed only in his imagination. His related claims–25 million nonprime loans and 10 million nonprime and other weak loans at the GSEs–seem to rely on a pretext that he concealed from readers of The Wall Street Journal. He defines “subprime,” “Alt-A” and “nonprime” differently from just about everybody else.

How Nonprime Loans Suddenly Tripled

Wallison is a fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, where his colleague Edward Pinto came up with new definitions, that effectively tripled the number everyone else uses, from about 8.8 million “self-denominated” nonprime loans (6.7 million subprime and 2.14 million Alt-A), to 26.7 million loans. In the AEI’s parallel universe, almost half of 55 million mortgages in America are nonprime. Pinto used much broader criteria–essentially including anything with subprime or Alt-A “characteristics”–to arrive at his total.

Whatever the merits of Pinto’s approach, it’s important to highlight why Pinto is talking about something very different from everyone else. Nobody else uses Pinto’s definitions, not the GAO, not the St. Louis Fed, not the FHFA, not the Mortgage Bankers Association, not the New York Fed, not Moody’s, not the Federal Reserve. When most people talk about subprime and Alt-A, they aren’t talking about half of all U.S. mortgages; they are talking about a small percentage of mortgages that have proved to be extremely toxic, because they were likely to have been predatory, induced by fraud and/or extended without consideration of the borrower’s ability to pay.

The difference between Pinto and the rest of the world can be shown graphically. For everyone else, the issue is framed this way:

Nonprime mortgage growth in the first half of the 2000s was explosive as measured by dollar volume and as a share of refinance and home purchase loans (Figure 1-3). Subprime mortgage loans moved from being a niche product to being widely distributed to borrowers of all income levels beginning in 2000.

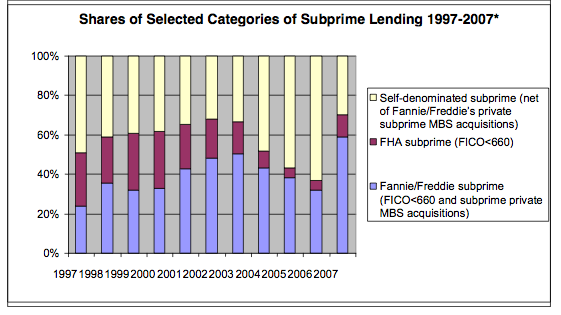

Pinto tries to give the impression that the GSEs were flooding the market with subprime and Alt-A for years and private lenders took a majority market share for the first time in 2005. The chart below is from his “forensic study” of “Government Housing Policies in the Lead-up to the Financial Crisis.” What kind of study would sidestep the issue of fraud and government laws against fraud? Pinto’s study, the analog to Wallison’s op-ed piece and “primer.”

Under Pinto’s approach, any loan to a borrower with a FICO score below 660 is “subprime,” period. Similarly, Pinto deems any loan originated with a combined loan-to-value of 90% or more–say, an 80% first lien, 10% second lien–to be “Alt-A,” period. Similarly, any loan with an initial below-market teaser rate is Alt-A, period.

Pinto’s categorizations are, to put it charitably, misleading because they obscure the impact of the GSEs’ credit practices, which were to limit exposure to loans that had not been adequately underwritten with full documentation and consideration of a borrower’s ability to pay. A fully conforming fixed-rate 70%-LTV mortgage loan, originated with full documentation to a borrower with a 650 FICO score, is not normally considered subprime. Similarly, a fully conforming fixed-rate 90%-LTV mortgage loan, originated with full documentation to a borrower with a 790 FICO score, is not normally considered Alt-A. Also, any GSE financing in excess of 80% is covered by private mortgage insurance; Fannie and Freddie are not allowed assume credit risk beyond 80% of a home’s appraised value. Most Alt-A loans, under everyone else’s definition of the term, are low-documentation, or liar loans.

Private Label Deals Are Exponentially Worse

Data released by the FHFA, which compares GSE loan performance with that of private label deals, highlights the reason why everyone else’s definitions are more edifying. The FHFA compared loans according to four salient criteria: FICO scores, LTV at closing, vintage (year of origination), fixed-rate versus ARMs. The overwhelming majority of GSE mortgages were fixed-rate, whereas the overwhelming majority of loans packaged by Wall Street into private label mortgage securitizations were adjustable-rate. ARMs–both prime and nonprime– performed exponentially worse. Overall, the private label deals had delinquency rates that were four to five times higher. When compared on an apples-and-apples basis, the GSE loans almost always performed better than those in private label deals.

The FHFA data points to one of the fatal flaws in private label securitizations, which became apparent when home prices started falling. The deals were structured so that no one could act like a bank; that is, it was difficult, if not impossible, for somebody to come in and negotiate loan workouts with the borrowers. With these deals, no one is really in charge of maximizing loan recovery, and conflicts of interest abound. Nobody knows who really owns the different securitization tranches, or who is betting on failure through a secret credit default swap. Private labels deals, at least those outside of GSE lending guidelines, did not really exist during the last real estate downturn in the early 1990s. But again, the issue of wall street promoting flawed structures is banished from AEI/GOP universe.

Once Again, Debunking The Fannie/Freddie Myths

Needless to say, Pinto’s skewed analysis, which argues that the slide in lending standards was driven by the GSEs, is refuted by various studies, such as “Understanding The Boom And Bust In Nonprime Mortgage Lending,” which was prepared at Harvard with the assistance of advisors from the FDIC, the Federal Reserve and elsewhere. The study used data produced under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act. It dispels the myth that subprime loans (using the non-Pinto definition) were synonymous with low-income borrowers. Circling back to an earlier quote:

Nonprime mortgage growth in the first half of the 2000s was explosive as measured by dollar volume and as a share of refinance and home purchase loans (Figure 1-3). Subprime mortgage loans moved from being a niche product to being widely distributed to borrowers of all income levels beginning in 2000. Though a disproportionate share of subprime mortgages were originated to lower income and minority households, the majority of all such loans were taken out by middle-income white households. Even at the peak in 2005, Home Mortgage Disclosure Act data shows that only about a quarter of all higher-priced home purchase loans were made in low-income communities, only a third in majority-minority communities, and only a fifth in low-income majority-minority communities. [Emphasis added.] p.38.

It also refutes the idea that nonprime mortgages, (again the non-Pinto definition), were dominated by the GSEs:

HMDA data suggests that the GSEs directly purchased only 1.7 percent of the 1.3 million higher-price loans issued in 2004. Higher-price loan specialists sold only one-tenth of a percent of their loans directly to the GSEs, but 64 percent of their loans to private conduits.

Information reported under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act provides a window on the mortgage market in 2005…It also reveals just how little higher price lending was done by CRA lenders in their assessment areas and how much more likely higher priced loans were to be sold into private label securities than held in portfolio or sold to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. [Emphasis added.] p.44.

That’s why it makes no sense to conflate the toxic mortgages packaged by Wall Street with the distressed loans extended by the GSEs.

Distracting Away From A Legacy of Failure

Why is Wallison so invested in this conflation? Because, as a member of the Shadow Financial Regulatory Committee of the American Enterprise Institute, he spent the last nine years advocating policies that promoted the spread of toxic mortgages and denying the damage that they caused. Check out the Shadow Committee statements here, here, here, and here.

If you suspect that Wallison learned anything from the FCIC hearings on mortgage fraud, watch this.

Clarification/Correction: Recently, I stumbled upon an article in About.com that misquoted an article written by Wallison and Charles Calomiris about losses at Fannie and Freddie. The misquote had gone viral, in part because the presentation of numbers was somewhat misleading. So I wrote an article in this site and elsewhere wrongly claiming that Wallison and Calomiris, “lied” about that particular data. Upon correcting my mistake, I suggested that Wallison intended to mislead others with his presentation of his numbers. At that time, I neglected to mention that my belief was based in part on the numerous false and misleading claims that Wallison had made elsewhere. I regret the error.